The holy-rolling and guitar-swinging hymn singer who arguably gave birth to rock and roll and was buried in an unmarked grave for more than 35 years is finally getting the respect she deserves. For the fans of Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1915-1973), the posthumous adulation is bittersweet.

Ignored and neglected for decades, she was finally inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame on April 14. “She is the founding mother who gave rock’s founding fathers the idea,” the Hall of Fame acknowledged. Sister Rosetta’s obscurity is both regrettable and pitiable. Her music and talents were gender-eclipsing, genre-defying, and ground-breaking. She was a finger-picking, gospel-rocking trailblazer on the guitar long before Jimi Hendrix, Chuck Berry, or Eric Clapton.

“Sister Rosetta Tharpe holds an important role in the evolution of American music; a great innovator, she not only unapologetically bridged the seemingly enormous chasm between secular and church music, she also helped pioneer the unique sound of rock-n-roll guitar,” Rhiannon Giddens, lead singer of the Grammy Award-winning Carolina Chocolate Drops, has observed. “Her infectious spirit, impeccable musicality, and sheer joy in her faith are obvious in every recording and are a source of great inspiration.”

Tharpe grew up in a conservative church setting that was simultaneously progressive about women in ministry, loud musical instruments, and an expressive worship style that encouraged hand clapping and dancing. In some quarters, this lively expression was looked down upon and dismissed as holy rollin’, but this was the high-octane incubator for Rosetta that gave her a platform to express herself as a young girl.

Tharpe’s mother was a mandolin player and a traveling evangelist with the Church of God in Christ, the African-American Pentecostal-Holiness denomination founded in 1897. Accompanying her mother, Rosetta began playing “Jesus on the Mainline” on the guitar at age four. After years of playing in revival meetings and church services, Rosetta moved to New York City in 1938 and became the first gospel artist to be signed to Decca Records. She performed with Cab Calloway at Harlem’s segregated Cotton Club and was featured at John Hammond’s “From Spirituals to Swing” sold-out event at Carnegie Hall.

“She sang some gospel songs that brought the house down,” Count Baise recalled. “She sang down-home church numbers and had those old cool New Yorkers almost shouting in the aisles. There were lots of people out there who had never heard that kind of singing, but she went over big.”

Sister Rosetta’s star was on the rise. She was, after all, the first solo gospel artist to play at the famous Apollo Theater in Harlem. While the white audiences were thrilled to get their first listen of African American gospel music, many of her church supporters were aghast that she was taking what was known as “sanctified” music into nightclubs. Walking the tightrope between the tabernacle and the spotlight – and making a living as a musician – would prove to be both a burden and challenge for her entire life.

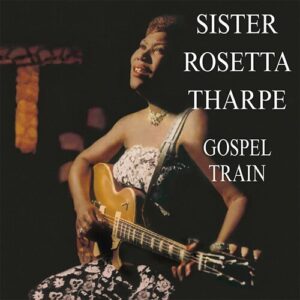

Sister Rosetta was famous for her raucous and rollicking music and mega-watt smile. But it was her guitar work that mesmerized audiences – saints, sinners, black, white, men and women. “Rapidly finger-picked notes press up against full-on power chords that linger languidly in the air,” Dr. Gayle Wald writes in her Tharpe biography Shout, Sister, Shout. “She squeezes notes from the high end of the pitch, relishing the gentle fuzz of distortion, then cajoles the instrument, commanding, ‘Let’s do that again.’”

In 1942, Billboard magazine called her music “rock-and-roll spiritual singing” – a decade before the phrase was commonplace. Tharpe attempted to “inhabit an in-between place where the worlds of religious and popular music intersected and overlapped,” Wald writes. “Even when limiting herself to a church repertoire, she stuck out as a loud woman: loud in her playing, loud in her personality. In concert, she combined the spontaneous fervor of religious revivals with the practiced production values of Broadway variety shows.”

The revolutionary nature of what she was doing was not unseen by up-and-coming superstars. “Sister Rosetta Tharpe was anything but ordinary and plain,” said Bob Dylan. “She was a powerful force of nature.” She influenced Tina Turner, Aretha Franklin, and Karen Carpenter. “Say, man, there’s a woman who can sing some rock and roll,” Jerry Lee Lewis once said. “I mean, she’s singing religious music, but she is singing rock and roll. She’s … shakin’ man … She jumps it.” She was also Johnny Cash’s favorite artist.

“Elvis loved Rosetta Tharpe,” proclaimed Gordon Stoker of The Jordanaires, the back up vocal quartet for Presley. “Not only did he dig her guitar playing but he dug her singing too.” Before backing Elvis, The Jordanaires toured with Tharpe – flipping the cultural picture inside out as a white quartet sang back up for an African American performer.

In a belligerently segregated era, she was a striking figure with ornate sequined dresses, high heels, and accessorized by a Gibson SG guitar strapped over her shoulder. “As a black woman with few outlets for public speaking, Rosetta fashioned a distinct means to speak through her guitar,” Wald writes. “As a woman who could outplay her male counterparts, she managed the ‘threat’ of her virtuosity to men by undercutting it with disarming humor and a dose of feminine decorum.” Thankfully, modern day fans can watch a handful of grainy YouTube videos, including scenes from her gospel TV show.

Tharpe’s recording of “Strange Things Happening Every Day” in 1944 was the first gospel song to make Billboard’s “race records” Top Ten. A smart case has been made that this was the first rock ’n’ roll record. That’s why her fans find sweet comfort in the Hall of Fame nod. “All this new stuff they call rock ’n’ roll, why, I’ve been playing that for years now,” Sister Rosetta told the London Daily Mirror back in the 1950s. “Ninety percent of rock-and-roll artists came out of the church, their foundation is the church.”

The historic relationship between the church and rock has fluctuated between resentment to hostility – sometimes for good reason. Rosetta fought hard to stay in the good graces of the church that nurtured her. That didn’t always work out but she would be the first to remind the church that there must be some way for the glorious and joyful noise of ecstatic worship to be shared with those who will never enter a sanctuary. To those who would tell her “come out from among them and be ye separate” (2 Cor. 6:17), she might respond, “let your light shine before men, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven” (Matt. 5:15-16).

During one spat with detractors, she responded: “God has said, ‘If I am for you, I am more than the world against you.’ He has also said, ‘Hold your peace, I will fight your battles, and that is what I am going to do and carry on for the Lord.”

Sister Rosetta Tharpe suffered a stroke in 1970 and died three years later at the age of 58. Showbiz audiences rise and fall for celebrities. Her funeral was modest in comparison to her larger-than-life personality. Sadly, she was buried in an unmarked grave. As word of this travesty was discovered by fans more than 30 years later, money was raised for a proper tombstone. “She would sing until you cried and then she would sing until you danced for joy,” it is properly inscribed. “She helped to keep the church alive and the saints rejoicing.”

Steve Beard is the creator of Thunderstruck. This article appeared in Good News in 2018.