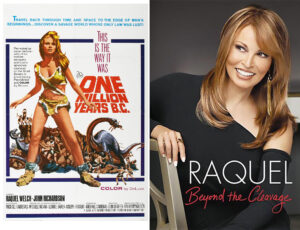

1966 movie poster for “One Million Years B.C.” and Raquel Welch’s 2010 cover her book “Raquel: Beyond the Cleavage.”

By Steve Beard

“Contrary to popular myth, I didn’t just hatch out of an eagle’s nest, circa ‘One Million Years B.C.,’ clad in a doeskin bikini …,” wrote Raquel Welch about her provocative cavewoman publicity photo for the 1966 film. “With the release of that famous movie poster, in one fell swoop, everything in my life changed and everything about the real me was swept away. All else would be eclipsed by this bigger-than-life sex symbol.”

That’s the way she launched her engaging 2010 memoir “Raquel: Beyond the Cleavage.” The Golden Globe-winning actress who appeared on stage and in dozens of films and TV shows died at her home in Los Angeles on February 15, 2023. She was 82.

Despite being the very definition of her generation’s bombshell, Welch never appeared in the nude for film or magazines, despite many lucrative offers. “I’ve definitely used my body and sex appeal to advantage in my work, but always within limits,” she wrote. “I feel strongly that a woman’s mystery is part of her appeal; and the power of the imagination is more potent and provocative than graphic on-camera sex or explicit nudity. I reserve some things for my private life, and they are not for sale.”

In her independent-minded book, Welch riffs on age, sex, hormones, showbiz, nutrition, parenthood, yoga, divorce, skin care, and religion. With a ringside seat during the advent of the sexual revolution, Welch is unflinching in her clash with a certain strand of brash feminism that rejected her vision of empowered femininity. “A sex symbol in the Age of Flower Children didn’t sit very well with the hardline feminists of the time,” she recalled. “They dismissed me as nothing more than a sex object. They didn’t look beyond the poster image to see what I was made of.”

It’s not hard to believe that she savored culture critic Camille Paglia’s description of Welch’s movie poster as “the indelible image of a woman as queen of nature. She was a lioness: fierce, passionate and dangerously physical.”

Her list of films included comedies, sci-fis, and westerns. Upon her passing, I watched a handful of her films (Fantastic Voyage, The Three Musketeers, The Last of Shelia, 100 Rifles, and The Biggest Bundle of them All.)

Her list of films included comedies, sci-fis, and westerns. Upon her passing, I watched a handful of her films (Fantastic Voyage, The Three Musketeers, The Last of Shelia, 100 Rifles, and The Biggest Bundle of them All.)

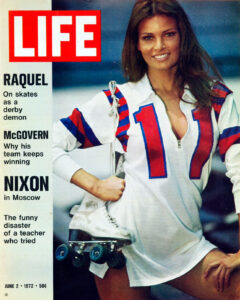

Welch’s screen credits also include the 1972 film Kansas City Bomber, a rough-and-tumble psychodrama of a single mother trying to make a living in professional roller derby (or perhaps it was symbolic of her own odyssey as a single mom struggling to make it in the entertainment industry). Welch trained on the bank track for three months and learned a slew of WWF-moves that were commonplace in the sport during that era (distinctly more anarchistic and pugilistic than the modern-day flat track version). Although she did have a stunt double for some of the action scenes, she actually broke her wrist during training. Rocky – her nickname from childhood – was no wallflower. She was all in.

The most endearing story in the book is when she is given some advice by the late Italian actor and director Vittorio De Sica. Early in her career, the two were working together in Rome and she was struggling to find her own “sense of style both on camera and in my personal life. I felt that the press was scrutinizing my every move as a newcomer, and I’d become painfully self-conscious,” she recalled. “I wanted to talk right, walk right, say my lines perfectly, look flawless, and somehow mask the fact that I was still green and inexperienced.”

Raquel Welch and Italian actor, Vittorio De Sica, in the movie “The Biggest Bundle of Them All,” 1968.

Vittorio took her aside and asked, “My darling girl, why are you trying to change yourself?” She responded with “something about needing to be perfect because everyone was watching me.” He laughed. “Ahhh, I see,” he said in his distinct Italian accent. “Please, my darling, do not try to be perfect – because the defect is very important.”

This came as sweet relief to the new starlet. “It was the best thing he could have said to me,” she wrote. “He opened my eyes to the fact that my authentic self, with all its flaws, real or imagined, was the most important quality I had to offer.”

In her memoir, she champions the importance of imagination and the cultivation of one’s own personal style. “Go to the theater, read a good novel, pore over art books, listen to all kinds of music, wander through flea markets, thumb through history hooks, travel. And visit museums,” she recommends. “Above all, allow yourself to daydream. These are not trivial pastimes. They are a means of making connections, of gathering inspiration and energy. You can’t invent anything of consequence – much less reinvent yourself – without exposing yourself to life.”

She also suggests stepping outside your comfort zone. Do you remember when Icelandic singer Björk showed up at the 2001 Oscars with a faux swan draped around her neck? At the time, it was all the chatter of the red carpet. “I loved Bjork for showing up at the Oscars draped in a swan fantasy, feathers and all,” Welch wrote. “Think how banal it would have been had she tried to fit in. Look, I’m not proposing that you drop acid and then get dressed, or force yourself too far out on a limb. But I am in favor of pushing the envelope a little to make a personal statement even if you make some mistakes. I know I did.”

Although she was an authority on beauty and fitness, Welch concludes her book with her spiritual journey. Understandably, the death of her mother sparked the contemplation of the hereafter. “When my tears had dried over her passing, I couldn’t stop thinking about what lies beyond that last breath. Strangely enough, I didn’t find these thoughts morbid,” she wrote. “Instead I found them welcoming and uplifting. I felt like a kid again, wanting desperately to know, who made the sky? What is God? And if he exists, I wondered what he had in mind for me.”

Perhaps surprising to some observers, Welch had deep reservations about the moral state of modern culture. “Seriously, folks, if an aging sex symbol like me starts waving the flag of caution over how low moral standards have plummeted, you know its’s gotta be pretty bad,” she wrote. “In fact, it’s precisely because of the sexy image I’ve had that it’s important for me to speak out and say, Wake up and take a long hard look at what’s going down.”

Earlier in her book, she writes about her loss of a moral compass by the time she left home at eighteen and being “influenced by the changing values of the ’60s. Swept along by the youth culture of the day, I started to seriously doubt whether there really was a God after all. I didn’t want to explore those doubts, but I found nothing in my life experience nor in the hedonistic philosophy of the ’60s that could rebut the disturbing question that glared at me from the cover of Time magazine, ‘Is God Dead!’ (1966). If this was true, what code of ethics should I then follow!”

As her sister Gayle faced surgery for ovarian cancer, Welch prayed for her survival. “At that moment, I was prepared to believe that there was something more than this lifetime … there had to be. Some things never die. It wasn’t logic that brought me to this sense of infinity,” she wrote. “I allowed myself to experience a primal instinct higher than thought. Call it a sense of wonder, that only a child would embrace.”

Welch’s sister recovered from the surgery. The experience convinced Welch that “when people pray in earnest, believing, it does make a difference. And why not? Some forces are beyond our understanding. As Pascal once declared, ‘The heart has its reasons, which reason knows nothing of.’ What I do know is that Gayle will always be with me, in this world and the next … God willing.” (Gayle Tejada died in 2020).

Growing up, the family attended a Presbyterian church in La Jolla and Raquel’s mother enrolled her kids in Vacation Bible School. The family was not particularly religious, Welch recalled, but her mom took the three kids to church every Sunday. Dad attended twice a year – Easter and Christmas.

“On the day my mother died, some years ago, I felt as if I’d lost my only connection with God’s favor,” wrote Welch. “I figured that any standing I had in the hereafter was based on the life she led, not on my inadequate attempts at following His principles. At the same time, I was reminded of my own mortality. I also thought back to the countless times she had taken me to church as a child and remembered the wonderful sense of peace I’d felt when sitting under the protection and grace of my mother’s faith. Now that I had lost my bearings, I wanted to reach out and touch the strong arm of God again.”

It had been five decades since she had regularly attended church. “I managed an awkward inept prayer to ask where I should look for such a sanctuary. It was embarrassing. I wasn’t sure exactly whom I was praying to anymore,” she confessed. “So I prayed to the God of my childhood and, lo and behold, he was still there. My journey had just begun.”

Outside Beverly Hills, the starlet found a small church “on the way to Pasadena, where the pastor and congregation were very devout and really knew their scripture. I had come there because I’d heard the pastor speak on the radio, and it sounded like he might be a good source of information. That turned out to be true. Apparently, even inept, awkward prayers are answered.”

Welch described the congregation as modest, unassuming, and friendly. “The people in this church weren’t Hollywood types,” she reported. “Even so, when I entered the chapel on that first day, I felt quite tentative. Maybe I didn’t belong among these people who actually practiced their faith. I didn’t look like them, sound like them, or act like them. I stood out like a sore thumb.” She sat in the back of the chapel.

“By the time the sermon was over, I felt remarkably comfortable sitting among these parishioners; not one of them gave me a second look,” recalled Welch. She found the members refreshing. “Not a superficial bone in their body.”

Without divulging the name of the congregation, Welch had found a spiritual home. “This is my church now. I have become a member of this parish and its people are my brothers and sisters in faith,” she wrote. “Together we form a fellowship where I can reaffirm my beliefs and worship every Sunday. When I’m in their midst, I’m just Raquel, not anybody special.”

This may have been the only location in Southern California where Raquel Welch was “not anybody special.” Counterintuitively, that must have been sweet liberation for a woman who had spent a lifetime under intense scrutiny and critique.

Welch concludes her book by encouraging her readers to think independently and form their own opinions and avoid getting “swept along by the herd when your instincts tell you otherwise. Most of all, I sincerely hope that each one of you finds the answers to your most ardent questions,” she concludes. “May those answers bring comfort to your heart and fulfill your soul.” According to her story, it certainly sounds like they did during her twilight years. RIP.

Steve Beard writes on faith and pop culture. He is the founder and curator of Thunderstruck.

Postscript: It was after I wrote my article that I learned that it was a Presbyterian church she attended in the last few decades of her life — just as she had attended as a child. After her death, religion writer Drew Dyck revealed on Twitter that the church she was referring to was a small Presbyterian church (“maybe 30 people”) that he also went to during seminary. He reported that she attended Bible study and described her as elegant, “sweet and unpretentious.” Christopher and Denada Neiswonger wrote a beautiful tribute to her on The Aquila Report. “She was of the old, rugged faith,” they wrote. “She never felt the need to pressure anyone in regard to matters of faith but she also didn’t have a great deal of patience for cute or pop cultural theological moods. This was part of her strength.”

Pingback: Thinking about God and Hollywood: Raquel Welch became a faithful Presbyterian? – Your Bible Verses Daily

Pingback: Raquel Welch became a faithful Presbyterian? — GetReligion - Minnesota Digital News

Pingback: Raquel Welch grew to become a trustworthy Presbyterian? — GetReligion – Expert Mind

Pingback: Raquel Welch became a faithful Presbyterian? — GetReligion - North Dakota Digital News

Pingback: Raquel Welch became a faithful Presbyterian? — GetReligion - Montana Digital News

Pingback: Raquel Welch became a faithful Presbyterian? — GetReligion - Missouri Digital News

Pingback: Raquel Welch became a faithful Presbyterian? — GetReligion - Newmexico Digital News

Pingback: Raquel Welch became a faithful Presbyterian? — GetReligion - South Dakota Digital News