November 18, 2005, National Review

Looking back on it now, it’s rather ironic that Johnny Cash scored such a major hit with the song “Walk the Line.” “I keep a close watch on this heart of mine / I keep my eyes wide open all the time / I keep the ends out for the tie that binds / Because you’re mine, I walk the line.” Ah, unhinged love – ideal and passionate.

Many fans think of Johnny singing, “I find it very, very easy to be true,” to his beloved June. Actually he wrote it as a pledge of loyalty to his first wife, Vivian Liberto. It was his song of fidelity. It’s no secret that when Johnny and June first fell in love, they were married to other people. The situation was a mess. He was strung out on pills, always on the road, and incapable of being the kind of father that his four young daughters deserved back home. There is no reason to sugarcoat it. Cash never did.

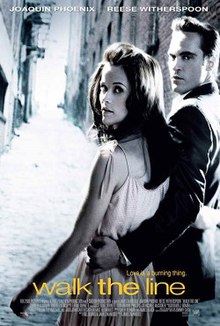

Brutal honesty is one of the admirable aspects of the movie Walk the Line, the fascinating and explosive bio-pic of Johnny and June Cash. His exploits on the dark side, as well as the scorching love he found in the arms of June Carter, are brilliantly illustrated in the film, starring Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon. Walk the Line only portrays a small sliver of Cash’s luminous and industrious career marked by bouts with the minions of hell and the fiery love of June and her parents, the musically trailblazing Maybelle and Ezra “Eck” Carter. The movie is high-octane Johnny Cash, warts and all.

Since the story is about the love affair between Johnny and June Cash, it should have properly been called Ring of Fire (“Love is a burning thing / And it makes a fiery ring / Bound by wild desire / I fell into a ring of fire”). It makes far more sense than calling it Walk the Line.

Let’s get this straight, Johnny Cash walked very few lines. Within the first two months of 1968, Cash’s divorce from Vivian Liberto was finalized, he performed at Folsom Prison, he proposed, and was married to June. As the two of them would sing, “We got married in a fever / Hotter than a pepper sprout,” for their hit “Jackson.” That was an understatement.

Walk the Line is a gut-wrenching story that causes anyone to squirm, and yet we love Cash. We always have. Perhaps we granted him grace in hopes that we too could find it for our own sins. St. Paul once confessed, “I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do” (Romans 7:15). If the Apostle could fall short, why would we be surprised that Cash got snagged?

He was America’s blue-collar troubadour of tales of heaven and hell, murder and redemption, love and death, sin and salvation. He was never too proud to seek grace, but he would never pretend to be pious. He once referred to himself as a C-minus Christian–a believer who had nose-dived into the sumptuous buffet line of fame and fortune and was working his way towards paradise, one painful day at a time.

He had an image that was one part Old Testament prophet and one part outlaw, a man who could sing about the Second Coming and killing your lover on the same album.

Long before he got the opportunity to portray the man in black, Joaquin Phoenix was invited to a meal with Johnny and June. After dinner, Cash picked up a guitar and sang “On the Banks of the River Jordan” with his wife. “To see them look into each others eyes while they sang that song was magical,” Phoenix told me during an interview. “It was absolutely magical.”

Moments after singing the gospel song, Cash quoted verbatim the most sadistic lines Phoenix had recited in Gladiator: “Your son squealed like a girl when they nailed him to the cross. And your wife moaned like a whore when they ravaged her again and again.” Cash told him it was his favorite part of the movie. The experience “encapsulated Johnny Cash to me,” Phoenix said. “Those two separate forces that lived equally inside of him. It really is night and day…He seemed to relish the dialogue as much as he did looking in June’s eyes and singing that song.”

That was Cash.

My church-going friends are going to be frustrated by the movie’s timeline. Walk the Line ends right about the time Johnny and June get married, so that you never really get to see a full-orbed picture of the religious side of Johnny Cash – the Billy Graham crusades he participated in, The Gospel Road film he financed, the book on St. Paul he wrote. In the film, you see plenty of the pill popping but none of the Bible-thumping.

The video for Cash’s version of Trent Reznor’s “Hurt” actually gives a more holistic vision to Cash’s life. Footage was gleaned from his early years, prison concerts, walking through the Holy Land, and hopping a boxcar. Cash is shown sitting behind a piano as well as strumming his guitar in his all-so-familiar black apparel. Interspersed throughout the video is the backdrop of the famous House of Cash museum in Tennessee – sitting in disrepair, closed to the public since 1995. The museum served as a metaphor for Cash’s physical condition, which at that time was weak and in pain. The face of Jesus appears; first, in a portrait and later in footage taken from Gospel Road, a movie on the life of Christ that Cash produced with his own finances in the 1970s. The graphic crucifixion scene is interspliced with concert footage and cheering prison crowds in order to poignantly emphasize that all of humanity carries the responsibility of Christ’s death.

When asked about the absence of faith in the latter half of the movie, Walk the Line director James Mangold acknowledges that “the part of John’s story that we’re telling about is the part where he pushed God away. And really, God started coming back to him, as did belief and love and life and living and art at the point the movie ends. So it’s hard to stick it in a place where a man who’s lost, taking pills, and trying to destroy himself is not a man who you can just easily stick in a scene of faith.”

Mangold has a point. There are glimpses. June drags Johnny to church as he is trying to kick his habit (that would have been November 5, 1967). In one of the best scenes, Cash is trying to convince the studio executives to let him record in prison. One of the executives says, “Your fans are church folk, Christians. They don’t want to see you singing to a bunch of murderers and rapists, trying to cheer them up.” Cash replies, “Well, they’re not Christians then.”

In another scene, Jerry Lee Lewis is carrying on about how they are doing the work of the devil and leading everyone to hell. In the movie, June quiets him down by asking if she is going to hell. When Cash used to tell this story, it was him who countered Jerry Lee by responding: “I’m not doing the devil’s work. I’m doing it by the grace of God because it’s what I want to do.”

Walk the Line powerfully reveals the depth of rejection that Johnny felt from his father. According to Mangold, Cash “wanted to make sure that his relationship with his father was done right. He had both very powerful, positive feelings about his dad and was very conflicted about that relationship. He wanted to make sure both aspects were explored.”

At the same time, the film attempts to beautifully display the love that the Carter family had for Cash. But once again, you cannot comprehend Johnny’s redemption apart from the fact that they all prayed like Pentecostals facing a tornado. They cared deeply for the man who would eventually marry their daughter. They understood his addiction and did everything they could to help him beat it.

Sometimes he would come bursting into their house drugged out of his mind. His eyes would bulge and his legs would flail as he paced around the house. Maybelle would quietly and calmly try to talk to him. All the while, Eck would say, “The Lord’s got his hand on Johnny Cash and nothing’s going to happen to him. The Lord’s got greater things for him to do.”

In some ways, Eck Carter was able to see more in Johnny Cash than we are in the film. Despite its gaps and shortcomings, however, Walk the Line is powerful and electric – the kind of movie that Johnny Cash could appreciate, warts and all.

–Steve Beard is the creator of Thunderstruck.