By Steve Beard

I know next to nothing about business – but Paul Van Doren clearly did. He was the founder of Vans, one of the most successful shoe, streetwear, and lifestyle brands in American history.

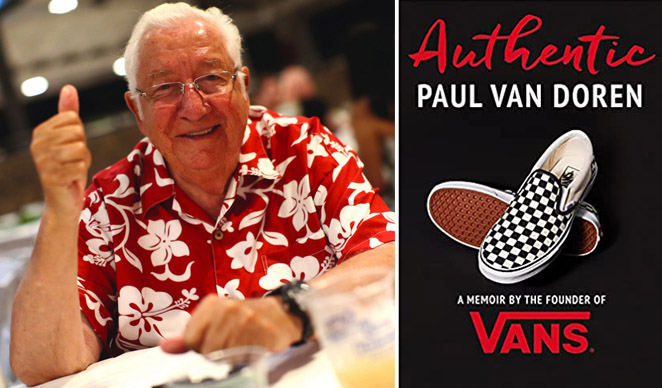

On May 6, Van Doren died at age 90. He had just completed his autobiography, Authentic: A Memoir by the Founder of Vans, shortly before his death. “With success comes reputation, and with hardship comes character,” he wrote. “Even when a cost is high or seems too high, it’s the downsides that create the most extraordinary upsides.”

From a gritty storefront and factory in Anaheim, California, Van Doren leveraged his small family-based shoe brand in the 1960s into a globally-recognized name synonymous with the individuality and creativity of action sports, music, art, and street culture. Tapping into the synergy of the Southern California surf and skate culture, the company today generates more than $2 billion in annual revenues. (VF Corporation – Dickies, The North Face, Timberland – purchased Vans in 2004 for $396 million.)

On a book jacket blurb for Authentic, skate legend Stacy Alva called Van Doren an inspiration. “He’s proof of the American dream. A mentor and fearless leader, and last but not least, the father we all love and respect,” said Alva.

I grew up in Southern California and gave up skateboarding decades ago, but I never outgrew my Vans – the colorful canvas and vulcanized rubber waffle-soled shoes worn by legions of fans around the globe. The company has 18 million Instagram fans and twelve million US Vans Family loyalty members. Believe it or not, it’s not uncommon for Vans to accessorize a wedding gown or a prom tuxedo. The shoes pop up everywhere.

Shortly after the Houston area was devastated by Hurricane Harvey in 2016, Vans hooked up with furniture magnate and humanitarian Jim McIngvale (aka “Mattress Mack”) to distribute more than 7,000 pairs of shoes. Steve Van Doren, Vans vice president and founder’s son, called McIngvale: “I’m heading your way. I got shoes.” Mack replied, “I got people.”

After they struck up a relationship, McIngvale called about buying 14,000 pairs of shoes. Vans donated the shoes. Mack ended up buying $87,000 worth of gift cards to give to employees and those in the Houston area who needed them. Mack, a deeply beloved Texas entrepreneur, was presented with an award at the following Vans annual sales meeting.

There is a long and colorful history behind the shoes made by Van Doren for notables such as legendary Hawaiian surfer Duke Kahanamoku (U.S. Open of Surfing in 1964) and skateboard superstars such as Stacy Peralta, Tony Alva, Steve Caballero, and Christian Hosoi.

Nothing, however, catapulted Vans into the worldwide spotlight like having its checkerboard shoes worn by actor Sean Penn (playing Jeff Spicoli) in the 1982 film “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.”

Penn’s character serves as the film’s comedic relief as a loveable stoner. In one scene, he takes one of the shoes out of the iconic Vans box and bonks himself on the head. “If there was ever a character custom-made to wear our shoes, it was Spicoli,” wrote Van Doren. “Not only did he skate and surf, but he was also in a band … an off-the-wall individual who was always his own man, much to the frustration of his teachers. He did whatever he wanted, even having pizza delivered to class.”

Spicoli may have served as the perfect Vans ambassador for a 1980s teen comedy, but Van Doren wisely parlayed that publicity into a fortune through old-school virtues. “My parents taught me long ago that people were the most important thing in your life – more important than money or prestige or possessions,” wrote Van Doren. “My father believed that family always came first. … My father never preached; he practiced. He often quoted the Golden Rule of ‘Do unto others’ and he always insisted on doing the right thing.”

His no-nonsense business memoir is punctuated with chapter headings such as Be Authentic, Respect the Workers, Never Waste an Opportunity, Listen to Your Customers, Sell What You Believe In, Embrace Change, and Get Back to Core Culture.

“Much of Vans’ early success was the happy result of hard work and creative troubleshooting,” Van Doren wrote. “It helps that we knew our customers, especially the skaters and the surfers and the moms. It helps that we cared about making a really good quality shoe at an affordable price, and to give exceptional customer service – always.”

Van Doren soberly realized that other companies were filling the conventional market for track and field, football, baseball, and basketball. Vans targeted the exploding alternative action sports market by launching the Vans’ Triple Crown competitions for skateboarding, snowboarding, wakeboarding, surfing, and BMX. “Until the skateboarders came along, Vans had no real direction, no specific purpose as a business other than make the best shoes possible,” Van Doren wrote. “When skateboarders adopted Vans, ultimately, they gave us an outward culture and an inner purpose.”

Vans had big ears to hear what the customer was saying. “If it’s a checkerboard, if it’s bright pinks and yellows, or if it happens to be dinosaurs or a skull and crossbones, listen to their two cents’ worth about colors and designs and what they think a graphic should look like on a shoe or a shirt,” he advised. “Pay attention to the people using your product – or even better, work with them to create something completely new.”

That is exactly how the checkerboard design emerged decades ago. Van Doren’s son, Steve, noticed that some of the students from Huntington Beach High School began drawing checkerboards on the top of their shoe canvas. In 1981, Vans began offering the black-and-white checkered pattern as an option for their classic slip-ons. The unique design proved to be exceedingly popular.

“In London around this time, the second wave of Jamaican ska music was rocking the city,” writes Van Doren. “The mix of punk rock with Caribbean melodies came to be known as the ‘two-tone wave’ because of its combination of typical ‘white’ and ‘black’ sounds. I was told the Vans’ checkerboard pattern came to represent the breaking of racial barriers and intermixing of styles, making it the ideal fashion statement for this particular music subculture.”

The Vans stake in alternative music promotion and helping launch fledgling garage bands was a full-scale investment. Every summer, Vans sponsored the Warped Tour from 1995 to 2019. Crisscrossing the United States for 25 years, it was the largest travelling music festival in rock ‘n’ roll history.

In addition to the sports and music marketing, Van Doren makes it clear that dependable relationships within the business enterprise sparked the growth of Vans. “Find honorable people to be your partners, work with creative people, and be fair. Be kind,” he wrote. “In other words, don’t be a jerk. Stand up for others. Until our last breath, we can do something good for someone else.”

Authentic delves into the innovative brainstorms and intense challenges he faced in business – including the time he had to come out of retirement to lead Vans through a startling bankruptcy in 1984. “Ecstaticism isn’t a word but should be. … It’s what distinguishes determination from grim determination. When we survive things like depressions, pandemics, and bankruptcies, what’s left to savor is that much sweeter. We wouldn’t look back. At Vans, we would never head that way. No matter what, we would always keep pushing forward.”

Vans was always much more than a sneaker brand to its founder. “Five decades after I started the Van Doren Rubber Company, our brand is associated with ‘expressive creators,’ the artists, musicians, skaters, and surfers – the trendsetters, the ones who go their own way,” concluded Van Doren. “I could not be prouder, because that’s how I always did things, too.”

Steve Beard is the curator and creator of Thunderstruck and a roller derby photographer.