If you’ve seen the movie Crash, there is a scene in which Anthony, a car thief, discovers a van with the keys dangling in the driver’s door. Since no one is around, he hops in and drives to a chop shop to sell off the parts. When they open up the back of the van, Anthony and the shop owner are startled to find a dozen Asian men, women, and children. In stunning immediacy, the shop owner offers Anthony $500 for each one without a tinge of reluctance—haggling for humans like used auto parts.

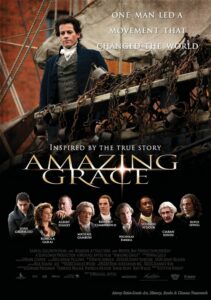

As the 2006 Academy Award-winning morality tale, Crash is loaded with gut-wrenching scenes meant to prick our racial prejudices and stereotypes. The chop shop scene came to mind while viewing Amazing Grace, a film about British abolitionist William Wilberforce (1759-1833). Available now on DVD, the movie’s release was timed to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in England. At that time, the British Empire was heavily dependent upon the slave trade and Wilberforce dedicated his entire life to fighting the gross social injustice.

Played by Ioan Gruffudd (King Arthur, Fantastic Four), Wilberforce was idealistic, compassionate, eloquent, and tenacious. The heir to a sizable fortune, he was elected to parliament at 23 years old (his boyhood friend was William Pitt, the youngest Prime Minister of Great Britain). After experiencing a dramatic spiritual conversion a few years after his election, Wilberforce struggled with his “secular” political vocation. He was not convinced that he could serve God and Parliament at the same time.

Wilberforce was ready to call it quits when he met John Newton (played by Albert Finney), a former slave ship captain and author of the beloved hymn “Amazing Grace.” First seen mopping the floor of a sanctuary in sackcloth, Newton is able to convince Wilberforce that combating slavery would be doing the work of heaven. “The principles of Christianity require action as well as meditation,” says Newton.

In their actual historic meeting, Newton told the young legislator: “God has raised you up for the good of the church and the good of the nation, maintain your friendship with Pitt, continue in Parliament, who knows that but for such a time as this God has brought you into public life and has a purpose for you.”

“When I came away,” Wilberforce recalled, “my mind was in a calm, tranquil state, more humbled, looking more devoutly up to God.”

Faith played a dramatic and pivotal role in Wilberforce’s actual life. While his conversion and prime religious motivation is treated respectfully in the film, it is purposefully low-key. For those who actually have read up on Wilberforce, the depiction is a considerably toned-down version of his religious pulse.

Despite suffering from perpetually bad health, Wilberforce even stopped taking the prescribed opium for his pain because it diminished his mental alertness and rhetorical agility. He collected evidence against the slave trade, introduced abolition legislation, and collected more than 390,000 signatures demanding its end.

Although his accomplishments and courage are celebrated in our modern era, Wilberforce was reviled by many within his contemporary British society. He was attacked in newspapers, physically assaulted, and forced to travel with a bodyguard because of death threats.

Nevertheless, he was encouraged by lovers of justice such as Newton and John Wesley, the founder of Methodism. Six days before his death in 1791, Wesley wrote what would be his final letter to encourage Wilberforce: “Unless God has raised you up for this very thing, you will be worn out by the opposition of men and devils. But if God be for you, who can be against you? Are all of them together stronger than God? O be not weary of well doing! Go on, in the name of God and in the power of his might, till even American slavery (the vilest that ever saw the sun) shall vanish away before it.”

The British slave trade was shut down in 1807 because of Wilberforce’s tireless efforts, yet he continued to work until the end of his life to completely abolish slavery in England. In 1833, a bill to outlaw slavery was finally passed. Wilberforce died three days later.

But even today the global battle against slavery is far from over. “Although most nations have eliminated servitude as a state-sanctioned practice, a modern form of human slavery has emerged,” declares the 2006 U.S. State Department “Trafficking in Persons Report.” “It is a growing global threat to the lives and freedom of millions of men, women, and children. Today, only in the most brutal and repressive regimes, such as Burma and North Korea, is slavery still state sponsored. Instead, human trafficking often involves organized crime groups who make huge sums of money at the expense of trafficking victims and our societies.”

The report profiles horrific examples: “Reena was brought to India from Nepal by her maternal aunt, who forced the 12-year-old girl into a New Delhi brothel shortly after arrival. The brothel owner made her have sex with many clients each day. Reena could not leave because she did not speak Hindi and had no one to whom she could turn. She frequently saw police officers collect money from the brothel owners for every new girl brought in.… Reena escaped after two years and now devotes her life to helping other trafficking victims escape.”

As tragic as her story is, Reena is one of the lucky ones. In researching his book Not For Sale, Professor David Batstone traveled to Cambodia, Thailand, Peru, India, Uganda, South Africa, and Eastern Europe to investigate modern-day slavery. His findings are alarming. “Twenty-seven million slaves exist in our world today,” he writes. “Girls and boys, women and men of all ages are forced to toil in the rug looms of Nepal, sell their bodies in the brothels of Rome, break rocks in the quarries of Pakistan, and fight wars in the jungles of Africa. Go behind the façade in any major town or city in the world today and you are likely to find a thriving commerce in human beings.”

The United Nations estimates that there are 10 million children being exploited for domestic labor. Hundreds of thousands of children are forced into domestic slavery in countries such as Indonesia (700,000), Brazil (559,000), Pakistan (264,000), Haiti (250,000), and Kenya (200,000). “These youngsters are usually ‘invisible’ to their communities, toiling for long hours with little or no pay and regularly deprived of the chance to play or go to school,” states a U.N. report. UNICEF estimates that 1 million children are forced today to sell their bodies to sexual slavery.

“The good news about injustice is that there is a God who hates it and wants to stop it,” says Gary Haugen, president of International Justice Mission. His organization of lawyers, criminal investigators, and social workers has been on the frontline to investigate human trafficking, collect evidence, and work with local authorities to rescue the victims and put the captors behind bars.

Abolitionists like Haugen are today’s Wilberforces. Despite the agonizing stories of slavery told in Batstone’s book, it really is a profile of the men and women who are using their unique skills and perseverance to fight injustice. “The women who embrace the child soldiers of Uganda move in a different universe from those abolitionists in Los Angeles who confront forced labor in garment factories,” he writes. “A Swiss-born entrepreneur launches business enterprises for ex-sex slaves in Cambodia, while an American-born lawyer uses the public justice system to free entire villages in South Asia.”

At the conclusion of Crash, Anthony finds a moment of redemption by freeing the Asian slaves from the back of the van. That cinematic scenario is what modern-day abolitionists hope will take place when human trafficking is widely publicized.

In his first speech to Parliament regarding the slave trade, Wilberforce described the unfathomable conditions upon the slave ships and the despicable practice of slavery. After three hours, he concluded by telling his colleagues: “Having heard all this you may choose to look the other way, but you can never again say that you did not know.” The producers of Amazing Grace hope to relay the same message.

Steve Beard is the editor of Good News.