Sinead O’Connor: A second listen

Sinead O’Connor: A second listen

2007 —

[Editor’s note: This column was written more than 10 years before Sinead O’Connor converted to Islam in 2018.]

Some of my churchgoing friends were perplexed by my recent praise of Sinead O’Connor. They still have visceral memories of a brash young woman tearing up a picture of Pope John Paul II on national television fifteen years ago.

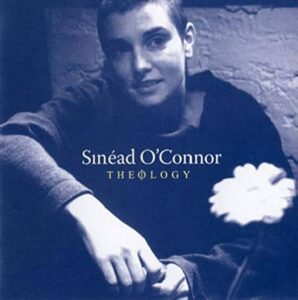

While their reaction is understandable, I have asked them to lend her an ear. Quite literally, I have encouraged them to listen to her new double album Theology — a stunning collection of songs taken from the Old Testament books of Psalms, the Song of Solomon, and Samuel. Also on the album are covers of “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” from Jesus Christ Superstar and Curtis Mayfield’s “We the People Who Are Darker Than Blue.”

Even though Theology will most likely not be sold in those well-manicured religious book stores, it is a soulful and contemplative masterpiece. Back in the 90s, I was struck by the way her powerful vocals reverberated through every note of her 1990 mega-hit “Nothing Compares 2 U” written by the equally enigmatic Prince. The song’s unforgettable video focused entirely on her face and culminates with a lone tear rolling down her cheek. I was mesmerized by her eyes, conviction, and dagger-through-the-heart intensity.

Even though Theology will most likely not be sold in those well-manicured religious book stores, it is a soulful and contemplative masterpiece. Back in the 90s, I was struck by the way her powerful vocals reverberated through every note of her 1990 mega-hit “Nothing Compares 2 U” written by the equally enigmatic Prince. The song’s unforgettable video focused entirely on her face and culminates with a lone tear rolling down her cheek. I was mesmerized by her eyes, conviction, and dagger-through-the-heart intensity.

Along with her shaved head, O’Connor has always been recognized for her righteous indignation. She won a Grammy for “Nothing Compares 2 U,” but boycotted the awards ceremony because of its commercialism. O’Connor refused to appear on Saturday Night Live with misogynist comedian Andrew Dice Clay. She disallowed the traditional recording of the American national anthem to be played before a concert in New Jersey.

When she did finally agree to being the musical guest on Saturday Night Live, she committed an incendiary protest that had all the subtlety of a car-bomb. During a version of Bob Marley’s “War,” she added several unscripted references to child abuse and as she sang the final verse, O’Connor tore up a picture of the Pope.

The phone lines at NBC were scorched by thousands of angry callers. To this day, the network refuses to rebroadcast the footage. Two weeks later she was booed off the stage at a Bob Dylan tribute concert in Madison Square Garden.

American fans were bumfuzzled at her vitriolic protest. They largely had no idea that her actions were targeted toward scandalous reports in her home country of Ireland regarding abuse committed by priests. O’Connor believed that the Vatican had been covering up the allegations and silencing the families of the victims.

Irish playwright Sean O’Casey once said, “It’s my rule never to lose me temper till it would be detrimental to keep it.” Sinead reached that point. She was Catholic by birth, culture, and blood. O’Connor was grief-stricken and enraged to think that men of the cloth would violate the innocence of devout children — a sobering and volatile emotion that American churchgoers have had to experience for themselves in subsequent years.

Compounding the news of the scandal in Ireland, O’Connor was dealing with the residual pain of her own abusive childhood. In talking with Risen Magazine, O’Connor said that in the midst of her traumatic upbringing she formed a very tight relationship with God. “When I was being set upon I used to see Jesus in my mind, in particular the crucifixion,” she said. “And I would see Jesus’ blood coming from his heart to mine and that gave me the ability not to feel pain. So I really do believe in Jesus as savior from that point of view.”

Five years after the tumultuous Saturday Night Live taping, she asked the Pope to forgive her. In an interview with an Italian newspaper, O’Connor said that tearing up his picture was “a ridiculous act, the gesture of a girl rebel.” She claimed she did it “because I was in rebellion against the faith, but I was still within the faith.”

As time passed, O’Connor realized that as just as her cause and indignation may have been, the nature of the act would never be understood. A few years later, she reemphasized her assessment: “I’m sorry I did that, it was a disrespectful thing to do. I have never even met the Pope. I am sure he is a lovely man. It was more an expression of frustration.”

“I know that I have done many things to give you reason not to listen to me, especially as I have been so angry,” O’Connor sang on her 2000 album Faith and Courage. “But if you knew me maybe you would understand me/ Words can’t express how sorry I am if I ever caused pain to anybody/ I just hope that you can have compassion and love me enough to just please listen.” She was quoted in Rolling Stone at that time as saying, “If I want to get heard, it’s important that I accept humility.”

In her discussion with Risen, she said, “I usually find forgiveness easy because I have so much to be forgiven of.” From the beginning of time, there seems to be two irrefutable and universal human needs: love and forgiveness. Sinead O’Connor is no different than any of the rest of us in need of a second chance at grace — or, in her case, a second listen.

Make no mistake, O’Connor is more reform school than charm school. She is combative and contrite, brash and brilliant, tough and tender, intemperate and introspective, course and comely, radical and religious. She smokes like a freight train and curses like a drill sergeant. She finds solace in the book of Jeremiah and loves Bob Dylan’s Slow Train Coming. Dr. Phil would have a heyday sorting through her relationships (she has four children from as many different men). She’s an earthy punk rock mom trying to find peace in a war-torn world and grasping to strengthen her spiritual devotion when religion sometimes acts as if it doesn’t need God.

O’Connor is an astute student of world religions and was even ordained several years ago by the Latin Trindentine Church — a maverick Catholic offshoot not recognized by the Vatican.

Although she is remarkably candid about her controversial life, the one area that she refuses to discuss is her religious vocation. While recognizing that her course of action is not acceptable to Rome, she is adamant about not making a publicity issue of her ordination. Instead, she is quite content to say, “My singing is my priesthood.”

When you hear her new album, you might even agree with her.

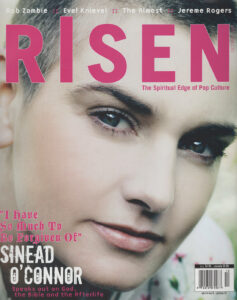

This column appeared in Risen Magazine in 2007.