National Review, January 20, 2006

Director Terrence Malick moves at a very distinct and deliberate speed – namely, his own. He’s not in a hurry. He wrote the screenplay for his latest movie The New World about twenty-five years ago. It has just now been released nationwide.

Despite widely heralded acclaim as a writer/director, Malick has only done a handful of major projects since 1973 (Thin Red Line, Days of Heaven, and Badlands). His style is very distinct, unconventional, and recognizable (some would say “slow and plodding,” while others might view it as “poetic and mystical”).

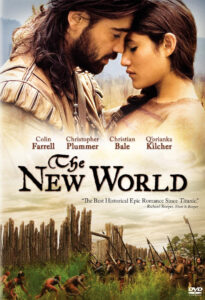

In his new film, Malick focuses his attention on the exotic story of Pocahontas (Q’orianka Kilcher), John Smith (Colin Farrell), and John Rolfe (Christian Bale) – a tale drenched with love, betrayal, sacrifice, deception, abandonment, and discovery. It attempts to chronicle the culture clash of European new comers and “the naturals” during the founding of the Jamestown Settlement in 1607.

The New World also tells the compelling story (through both fact and myth) of the cultural transformation of a young woman who has to give up her native food, faith, and fashion in order to fit into the colonial culture because of a courageous act of self-sacrifice.

“I think of Pocahontas as a visionary, a peacemaker ahead of her time,” fifteen-year-old Q’orianka Kilcher told me, “and living proof of how far the willingness of a dreamer of new worlds can go. I really admire her.” It comes through. For such a young actress, Kilcher communicates a tremendous respect and joy in portraying this legendary character.

The romance between the swashbuckling John Smith and the naïve Pocahontas is told through vignettes of love and discovery without verbalization. Be forewarned, a lot of the film is almost like a ballet – so much is intended to be communicated without using words. This will prove to be frustrating for some and liberating for others.

Viewers may sense that the film portrays all the British as bad and all the Native Americans as virtuous. It is far more nuanced than that, but there are several instances where John Smith’s voice-overs carry a dreamy adoration of the native culture. When I asked producer Sarah Green about the flowery language, she responded: “Most of our references were written accounts from that time from colonists, whether they were journal entries or letters from home or whatever. And several of those exact words were in those accounts, whether it was Smith or several of the other colonists. It reflects the naïve way that they saw the Native community at first.”

She went on to point out, “It’s only in the beginning when Smith is enamored of this world. We’re in his mind, experiencing what he’s experiencing that this is complete bliss. And as you can see, we show very quickly that that’s a much more sophisticated culture and that he was in fact naïve to think there was no jealousy. So those words are from the time. But I think the way Terry [Malick] uses those words shows there’s more to it than that.”

The film puts a heavy emphasis on having the viewer discover elements of life as if it were a maiden voyage. For example, at their first encounter in the tall grass near the riverbank, nearly naked Native American warriors sniff and poke at the sweaty, hairy, armor-clad explorers. The Powhatan tribesmen sport extravagant face paint and mohawks that, unfortunately, will likely lead many viewers to think of rowdy Oakland Raiders fans in the end zone. The naturals knock on the body armor of the European colonists as if they were knocking of the front door of their next door neighbors. It is almost comical to watch their facial expressions as they smell the stinky, white-faced sailors who have been trapped on a small ship for months without a bath.

This is Malick’s vision and, perhaps, the meaning of the title. It is a new world for everyone involved – new plants, creatures, foods, and smells. He is masterful at helping us explore a forest as if it were the first time we have walked through a shadowy section of trees or tromped through the swaying, thigh-high weeds near the river bank. Much of this is done through lingering landscape shots that seem more National Geographic than Hollywood.

As the film unfolds, we discover this new world through the eyes of John Smith as he explores the countryside with wide-eyed wonder. He lives with the Powhatans and learns their culture and way of life. In the second half of the movie, we see the world of colonial Jamestown (and later London) through the eyes of Pocahontas as she becomes a Christian and embraces British culture and colonial life.

“The clothes helped changed the way I was acting as Pocahontas,” Kilcher told me when I asked about her character’s cultural transformation. “In my traditional tribal clothes, I was able to run freely in the woods and do cartwheels and things like that. The first time I tried on my English wardrobe, I had them tie my corset extra tight and give me shoes a size too small in order to feel how constrained I imagine Pocahontas must have felt. I went home that night and cried because I felt like a caged bird, like the freedom was torn away.”

In one scene, Pocahontas (her name, at this point, has been changed to Rebecca) is shown being baptized. Her embrace of Christianity is synonymous with her need to wear uncomfortable and restrictive clothing, as well as adopt Victorian mannerisms. When asked if she thought this was a decision of religious conviction or simply the next step in adapting to the white man’s world, Kilcher said: “She had no where else to go. It was the next step. Once she decided to put on the English clothes and she was living with them, it was expected of her to become a refined Englishwoman named Rebecca and become baptized and speak proper English.”

When asked the same question, producer Sarah Green responded, “She was interested in Christianity. And she converted not just to marry John Rolfe or because she was a victim, but because she was drawn to that. I mean, that’s not the case obviously with many Natives where it was very different. So we simply show her in that process. That’s as much as we could really explore in this movie.”

It is not surprising the two women had such different responses to the same question—the very legend of Pocahontas conjures up varied responses from different groups of people. Was she a betrayer of her people, or was she a visionary peacemaker?

Christian Bale was asked what he thought his character John Rolfe, who eventually marries Pocahontas, found most attractive about her. “It’s the freedom of spirit,” he said. “It’s the courageousness, which I think Rolfe whilst he thinks about a great deal, he’s never actually acted upon. It’s something which has always been a theoretical ideal of what his true love of God and of people is meant to be, but it’s a brave soul who can actually act on that. And here he just sees a woman who’s just doing that every day of her life, every second.”

Starring in her first feature film, Kilcher is the bright light of The New World. While Farrell and Bale have the big-screen notoriety, she carries the freight as Pocahontas.

If you are looking for a documentary on colonial life, watch the History Channel. If you are intrigued by a poetic love and loss story with all the elements of out-of-the-ordinary filmmaking, make sure to catch Terrence Malick’s The New World.

Steve Beard is the creator of Thunderstruck — a website devoted to pop culture and spirituality.