By Steve Beard

By Steve Beard

September/October 2006

His lineage is country music royalty. His father was Johnny Cash, whose posthumously released American V: A Hundred Highways was recently #1 on Billboard charts. His mother was June Carter Cash, a member of the legendary Carter Family – pioneers of folk, country, and bluegrass music.

John Carter Cash was the associate producer of all his father’s American Recordings albums, produced his mother’s final album Wildwood Flower (2003), as well as The Unbroken Circle: The Musical Heritage of the Carter Family (2004). He was also the executive producer of the film, Walk the Line.

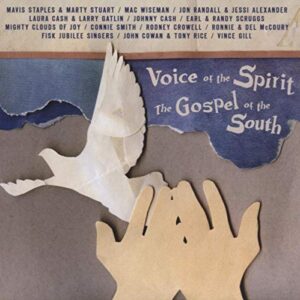

His most recent project as a producer is Voice of the Spirit: The Gospel of the South, a stunning compilation of bluegrass, country, and black gospel music. The album features artists such as Mavis Staples, Vince Gill, Earl Scruggs, Mighty Clouds of Joy, Del McCoury, Rodney Crowell, as well as his own father, Johnny Cash.

What follows is my conversation with John Carter Cash.

The blood in your veins is that of musical pioneers and legends. What was it like growing up hearing stories about the Carter Family and then living in the tornado that was the career of your mom and dad?

John Carter Cash: To be very honest, I took it for granted. It was just normal to me. I was surrounded by it all the time. I knew that they were larger-than-life figures and that many people – including my peers and fans and the press – looked up to my family. I had to mature in many ways before it really sunk into my spirit what it was all about. I learned to respect it, but it took awhile.

When you gained an appreciation of their reach and influence, was it liberating or confining? In other words, did you feel painted into a corner?

Early in my life it was that way. I felt as if I was surrounded by shadows and that I had to live up to a certain expectation. I think it was liberating, finally. When I looked at it in an intellectual sense, the Carter Family’s musical legacy is something that I was respectful of and proud of. As a producer, that’s where I found my peace. It’s looking into the past of music and finding a common thread that leads to the now, and into the future.

What is it about southern singers – perhaps your dad could be looked on as an example – who sang sanctified hymns and yet also seemed to relish in singing about cheating, drinking, and murder? [Laughter] There is something very unique about the southern artist’s knowledge and experience of sin and redemption.

Well, to know redemption, you have to know sin. We’re all light, we’re all dark. We don’t walk around redeemed and glowing. What we walk around as, hopefully, is an image of that redemption. If we were in all light, would anybody even notice? We have to go through the fire to gain our strength. That’s where that vision of redemption comes from-is through the pain, through the suffering. And that’s a commonality, that’s around the world with people. And everybody can relate to that. Yes, southern music has a lot of drinkin’, prison songs, and murder songs. But there’s something to relate to there for the listener. I’ve struggled through my pains. I’ve found redemption. And my greatness is because of someone bigger than me that forgives me.

It seems as if the Carter Family, and your father in particular, seemed to relish singing about both the sin and the redemption.

Yeah, that’s where my father got it. He got it from the Carter Family, from Jimmy Rodgers, from male black blues singers that would sing about redemption in one song and murder in the next. It’s an ancient, common thread, if there is such a thing in American music. My dad got it from others who came before him. It sort of became his stamped trademark.

The Carter Family recorded over 300 songs. One was gospel and the next would be a gallows ballad that the man would sing before he was hung for a murder that he had committed. Songs were written by the Carter Family post-mortem, after the character singin’ the song was dead. But that stems back from old English and Irish folk ballads. Redemption, pain, and suffering are common threads in the Carter Family’s music as it was in my father’s.

Your dad sings “Unclouded Day” on the album. What was that recording session like?

It was four days after my mother’s funeral. He wanted to record some from his heart. He kept on making music that day, recording five or six songs. “Unclouded Day” seemed to be perfect for this project.

The song was actually recorded in my father’s bedroom. It was therapy for him. To him, it was his way to continue to love my mother-to find a voice.

My father’s eyesight was fading and his passion before had come from reading the Bible. He couldn’t do that anymore. He could listen to music and he could sing. And so that was his way of continuance. His path to grieving was to continue to sing, to let his spirit express itself, to have something to look forward to, and to have something to plan on.

You’ve had three years to cope with the loss of your parents. Your father, in particular, was a larger than life King of the Jungle. But to you, he was your dad.

No matter the faith or the strength of the entertainer, we are all human. Under the man, I knew the simple man. The allure had long since past from my view of stardom. I knew the man in his simple form. But the lion I knew wasn’t based upon the way the world looked at him, it was based upon his continuance, the strength he had inside. He nearly died many, many times, and had risen back up through interior strength provided by God. And that’s who he was. That’s the lion. The lion, my father would have said, was not him. The lion was Judah, the lion was God’s strength through him.

Steve Beard is the creator of Thunderstruck. This interview appeared in Good News in 2006.