By Steve Beard

As I watched the evening news during the haunting first few weeks of the scorched-earth invasion of Ukraine, I could not help but see Kateryna Shadrina’s vibrant image of the Madonna and Child superimposed over the video footage on television of mothers carrying their young children in a panicked evacuation of their homeland.

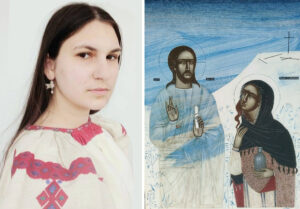

Although I have half-a-dozen depictions of the Mother and Child in my office, the liquid blues and electric yellows and oranges give Shadrina’s a different dynamic. The 27-year-old artist is an iconographer from Lviv, Ukraine.

Her image wreaked havoc on me.

Visual arts animate the imagination in ways that words alone cannot. To see Michelangelo’s Pietà – the sculpture of the lifeless body of Jesus being cradled by Mary after the crucifixion – is to engage a part of the mind and soul that mere nouns and verbs do not touch. Through painting, Van Gogh helped us visualize the story of the Good Samaritan, while Rembrandt illuminated the story of the Prodigal Son. El Greco told biblical stories in Spanish Renaissance fine art, Howard Finster preached the gospel through American folk art, and Marc Chagall challenged us to see the crucifixion from a different vantage point.

Let me be clear, I am not an art critic. I like what I like. But I also understand there is much to learn through the vision of an artist. “The first demand any work of art makes on us is surrender,” observed C.S. Lewis in An Experiment in Criticism. “Look. Listen. Receive. Get yourself out of the way.”

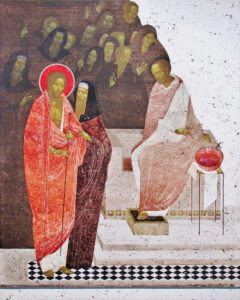

Four years ago, I was drawn to an essay written by John A. Kohan in Image journal about a new generation of young iconographers from Lviv. Icons are a very specialized field of religious visual art – a practice of spiritual devotion within the church dating back to the third century. Over time, stylistic peculiarities developed that differentiated icons from other forms of religious art.

Many of these contemporary Ukrainian artists are notably utilizing unusual color schemes and unexpected textures. The images are arresting and have nudged my own personal spiritual imagination in new ways.

Kohan – who had worked for Time magazine for more than 20 years and is an avid sacred art collector – had been drawn to this fresh expression of ancient spiritual artistry because of the “intriguing new variations on traditional tempera-painted holy images” and because the illustrations were being created on “unusual grounds like glass, found materials, and steel-and-copper-wire tapestry, all in an eclectic mix of abstract, neo-Byzantine, and Ukrainian folk art styles.”

His essay in Image was my introduction to the work of marvels such as Ivanka Demchuk, Lyuba Yatskiv, Natalya Rusetska, and Sviatoslav Vladyka. All these artists – and numerous others – are uniquely showcased by Iconart Modern Sacred Art Gallery in Lviv and its website (Iconart-gallery.com/en/).

After the invasion of Ukraine, the network evening news began broadcasting from Lviv – 40 miles from the border of Poland. That sparked my memory of Kohan’s Image story. The Rev. Kenneth Tanner, an old friend from college, also introduced me to a handful of other artists from Ukraine through Instagram.

While my low-church Methodist heritage does not offer a framework for iconography, I fully respect and appreciate that the imagery expresses a mystical spiritual dynamic for sacramental Christians that far defies the category of mere “beautiful art.” The pieces are often referred to as “windows to heaven.” Icons are meant to cultivate the soul and be an aid in prayer.

“I believe that art should testify of beauty. The search for it always leads to God as the original source – that is why I choose iconography,” observed Kateryna Kuziv (born 1993). “Beauty always points to something more, a sense of God’s presence. Creating icons for me is a pursuit of God, of paradise as a state of being with Him, a reproduction of the transformed reality, of the purified nature of humanity from sin.” (Her Facebook page.)

Other artists in this spiritual stream describe their work in similarly transcendent terms.

Natalaya Rusetska (born in 1984): “My art is about the eternal, the timeless, the extraterrestrial, the hidden. One of the inherent features of sacred art is symbolism. This is a figurative creation that reveals the inner essence of the depicted. Sacred art affects and changes the spiritual state of the human.” (Her Instagram page.)

Ulyana Tomkevych (born in 1981): “Painting the icon is the special conversation with the Lord and also with oneself. The silent prayer, that gives me the feeling of inner peace and harmony. This is the time for rethinking the Bible stories and the Ten Commandments in the context of the modern human life because the Bible is timeless. I think that first of all God is Love and Mercy. And the daily icon painting helps me to live my life with this understanding.”

A prescribed new vision

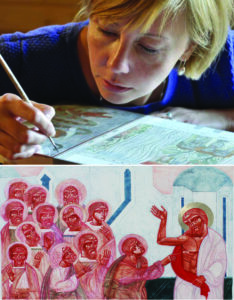

“My parents are doctors, so they did not plan for me to become an artist,” said Ivanka Demchuk in an interview with The Day several years ago. At a very early age, she had serious issues with her eyesight (astigmatism, farsightedness). Her ophthalmologist prescribed an intriguing treatment: “To increase the visual load in one eye, I had to obscure the other eye and then do a lot of painting, sculpting, and coloring. From that time on, I attended children’s art clubs, an art school, took an interest in classic paintings.” (Her Instagram page.)

Today, we are all the beneficiaries. Demchuk’s artistic imagination is on full display in a particularly captivating piece entitled “Hidden Life in Nazareth” portraying the holy family as Jesus takes his first steps as a toddler. In the background, there is laundry drying on a clothesline and a worktable with carpentry tools. I had never contemplated the first step of someone who would become known as “The Way” – but surely, there had to be one to be celebrated and pondered. Demchuk’s work helps give believers like me a more panoramic sense to the Incarnation.

Long before Putin’s bloody invasion of Ukraine, Demchuk (born in 1990) believed in the timeless relevance of stories such as the Good Samaritan and St. George the Dragon Slayer battling evil. In the context of the current barbaric war, some of her images take on even deeper significance and symbolism. “The evolution of human consciousness has not gone far enough to render us qualitatively different from people who lived two millennia ago,” she has observed. “We are facing the same problems and issues; we may become traitors just as those who crucified Christ.”

“A sword shall pierce your soul”

“Then Simeon blessed them and said to Mary, his mother: ‘This child is destined to cause the falling and rising of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be spoken against, so that the thoughts of many hearts will be revealed. And a sword will pierce your own soul too’” (Luke 2:34-35).

The soul pierce. What a gothic declaration to a young mother. Unlike any other human walking the earth, Mary knew Jesus with an unparalleled knowledge and intimacy. In understated fashion, the biblical text declares, “Mary treasured up all these things and pondered them in her heart” (Luke 2:19).

Kateryna Shadrina’s imagery of the Madonna and Child gives an almost expansive stargazing night scope to Mary’s experience. Mother and Child have been artistically portrayed since the era of the catacombs. The great poet Dante referred to Mary as “the lovely sapphire whose grace ensapphires the heaven’s brightest sphere.” Shadrina’s brilliant color scheme reflects that poetic sentiment. Her insightful artistic collection has rejuvenated my own spiritual imagination when I revisit biblical stories I have read for decades. (Her Instagram page.)

Shadrina’s exhibition at Iconart Gallery earlier this year was entitled “Victima” and reflected her views on sacrifice, faith, and love. In addition to her artistry, her thoughts on the subjects are equally compelling.

“Where there is true love, there will always be a place for sacrifice. Sacrifice can be considered as the level at which the power of love is measured,” she writes in the exhibit’s narrative. “And the standard in this is God – the perfection of love. He sacrificed the most precious thing for our hope. But in our pragmatic world, it is very difficult to weigh the pros and cons so that one’s sacrifice is not made in vain. We are focused on the terrestrial things, we catch the moment and don’t know exactly whether to think about the salvation of the soul and the kingdom of heaven.”

Art in bomb shelters.

Because missiles do not recognize beauty, truth, or faith, Ukrainians have been storing precious artwork in bunkers. “There is an egomaniac in Moscow who doesn’t care about killing children, let alone destroying art,” Ihor Kozhan, director of the Andrey Sheptytsky National Museum in Lviv, told the Washington Post. “If our history and heritage are to survive, all art must go underground.”

There are, of course, pieces of great beauty and value that cannot be hidden in bunkers. Statues have been wrapped in foam and plastic. “The stained-glass windows of the Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, founded in 1360, are covered in metal to protect them from Russian rockets,” reports the New York Times.

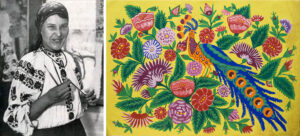

Early on in the invasion, Putin’s army targeted a museum in Ivankiv, 50 miles northwest of Kyiv. Housed in this seemingly insignificant civilian target were 25 paintings by Maria Prymachenko (1909-1997), a world-renowned Ukrainian folk artist who wowed both Pablo Picasso and Marc Chagall.

“The museum was the first building in Ivankiv that the Russians destroyed,” the artist’s great-granddaughter Anastasiia Prymachenko told The Times of London. “I think it is because they want to destroy our Ukrainian culture.”

In a truly heroic gesture, a friend of Anastasiia’s ran into the burning museum and saved as many of the artworks as he was able. “When he saw the smoke from the museum he ran, broke the museum window and went into the fire,” she reported. “He couldn’t take everything out but he knew the most famous paintings were by Prymachenko. Since he only had a few minutes, he just took these paintings, and a few other works of art.”

Prymachenko created brightly-colored mythical and fantastical creatures and her work was called primitive, naïve, or the “art of a holy heart.” With critically acclaimed exhibitions literally around the globe, she stated her motivation in utterly tender terms. “I make sunny flowers just because I love people, I work for joy and happiness so that all peoples could love each other and live like flowers on this Earth,” she once said.

Allowing art to shine

Christianity around the globe is largely represented by three major expressions: Catholicism, Protestantism, and Orthodoxy. Within Ukraine, the vast majority of the population is Orthodox. However, Ukrainian Greek Catholicism is the dominant expression of faith in Lviv and in much of western Ukraine (the “Greek” in the title is about its Byzantine liturgical worship style, not about Greek ethnicity).

The contemporary iconographers in Lviv come from a spiritual lineage of survival that knows what it is like to hold fast to life and faith underground. After World War II, Joseph Stalin mercilessly attempted to dissolve and destroy the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. It was forced to worship in clandestine secrecy. The sanctuaries, art, and treasuries were summarily confiscated and handed over to Moscow’s Orthodox Church.

“Harsh repressions followed,” observed Dr. Nadia M. Diuk, then vice president of the National Endowment for Democracy, in a 2016 Atlantic Council report. “Ukrainian Catholic priests were beaten, tortured, and given long prison sentences. Tens of thousands of religious laity met the same fate. UGCC Metropolitan Josef Slipiy was exiled to a hard labor camp in Siberia. The church went underground: services were held in the forests, or in private homes where they dared. Children were baptized in secret and religious rites performed clandestinely, while the Soviet state continued its assault on priests, monks, nuns, and the Catholic faithful, offering respite within the Russian Orthodox Church or repression as the price for refusal to cut ties with the bishop of Rome.” (Dr. Diuk, herself ethnically Ukrainian, died in 2019.)

In 1994, Jane Perlez reported in the New York Times: “While many priests died in concentration camps and believers were persecuted, it was the biggest underground church in the former Soviet Union. Rites were administered, priests ordained and bishops consecrated secretly during these years.”

Part of the legacy of Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika reforms in 1989 was the restoration of the legal status to this ruthlessly persecuted church. On August 19, 1990, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church received possession – once again – of the historic Cathedral of St. George in Lviv. Tens of thousands rejoiced inside and outside the reclaimed sanctuary.

It is not difficult to see the new generation of imaginative artists and iconographers as a significantly blossoming manifestation of relentless faithfulness during decades of Soviet suppression.

“The time when I create the icon is my way of praying, questioning, searching, the time of being with God, before God, the state of happiness and peace,” said Katheryna Kuziv about her art. “The aim is to express the ‘incarnation’ of God’s Word in a visual image, where a touch of God’s reality must take place to awaken a longing for God, to promote the pursuit of Him.”

Although once viewed solely as a distinct art form within Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, John Kohan (spiritualartpilgrim.com) has hopes that an ecumenical reappraisal is taking place with a new generation. “Expanding the range of prototypes of Christ, the Virgin Mary, angels, saints, and key moments in sacred history can only make these images, which are uniquely created for personal prayer and corporate devotion, more accessible to larger numbers of Christians – a development in sacred art-making, surely worth celebrating in the universal church,” he wrote.

During the 1990s, there was not a more popular art commentator on British television than the late Sister Wendy Beckett (1930-2018). For more than 40 years, she lived in obscurity as a reclusive nun devoted to prayer in the middle of the night. However, the plain-spoken elderly nun – an Oxford-educated amateur art historian – became a media sensation with her insightful BBC/PBS tutorials on various works of art – from cave drawings to Andy Warhol, including iconography.

While she had detractors, Sister Wendy most certainly understood the spiritual dimension of icons. She knew that the apparent surrealism was often utilized to invite our eye to gaze at a world unseen. “They are drawing us out of our worldly reality into their world, the true world,” she wrote in Encounters with God, “summoning us to leave behind all that is earthly and to breathe an air more pure than we can understand.”

Steve Beard is the creator of Thunderstruck.org.