By Steve Beard

Over the many months of the worldwide pandemic, our nation has weathered wildfires in the West, hurricanes in the South, “murder hornets” in the Pacific Northwest, stay-at-home orders, nationwide protests, shuttered business, postponed funerals, drive-up church services, video classrooms, mask mandates, and a deeply polarized election.

Lord, have mercy. It just seems exhausting to recount the events of the year. Even though the stock market continues to soar, the drive-up lines at food pantries have never been longer. There are a lot of conflicting messages to process.

Those in the white lab coats tell us that a vaccine is around the corner – but it is not here yet. Until it arrives, we wait. “How long, O Lord, how long?” we ask – six feet from our neighbor. These are the days we live in.

Somewhat fittingly, Sunday is the beginning of Advent, the start of Christianity’s liturgical year as a time of expectant waiting and preparation for the celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ at Christmas.

Waiting was one of the hardest aspects of Christmas as a child. There was such an allure to the wrapped packages under the tree. You could see but not touch. So close – and yet, so far away. It seemed absolutely nerve-racking as a child.

Preceding Advent, Thanksgiving will be celebrated. It will be different. It is everyone’s hope that it will be a one-off, an aberration. Many families have changed plans and will not be gathered around the same table – celebrating apart, perhaps on Zoom. There really is no good way to spin it. It just feels unnatural and ill-fitting. Like everyone else, I can’t wait for the day when social distancing is behind us.

The Apostle Paul wrote to strugglers like me, “Rejoice always, pray continually, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is God’s will for you in Christ Jesus” (1 Thessalonians 5:18).

In light of all going on around us, this is a flamboyantly counterintuitive impulse. Grousing and complaining are sure ways to gather an adoring and sympathetic crowd. Giving thanks in a certifiable gloomy time can too often invite eye-rolling. Nevertheless, the challenge remains to press forward with rejoicing, praying, and giving thanks.

When I was young, there was a song we sang at church:

When upon life’s billows you are tempest tossed/

When you are discouraged, thinking all is lost/

Count your many blessings, name them one by one/

And it will surprise you what the Lord hath done.

The song was written by Johnson Oatman Jr. back in 1897. Oatman was a local preacher in the Methodist Episcopal Church and wrote nearly 3,000 hymns and spirituals. His song may sound out of date to modern worship leaders, but its message of hope and inspiration is timeless.

“Count Your Blessings” concludes with this reminder:

So amid the conflict, whether great or small/

Do not be discouraged, God is over all/

Count your many blessings, angels will attend/

Help and comfort give you to your journey’s end.

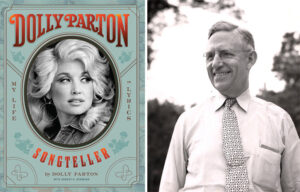

I was reminded of Oatman’s hymn as I thumbed through Dolly Parton’s new book Songteller: My Life in Lyrics – a 380-page collection of photographs and behind-the-scenes insights from dozens of her most well-known songs. As most fans know, Parton was born in a log cabin in East Tennessee without electricity. Her literal rags-to-riches story is an inspiration to fans across the spectrum around the world. Dolly has made it her life’s mission to be a contagious voice of encouragement, blessing, and gratitude.

One of the songs highlighted in the book is from her 1973 album, “My Tennessee Mountain Home.” It is a tribute to a Methodist minister and physician named Dr. Robert F. Thomas (1891-1980). After serving as a missionary in Denang, Malaysia, Thomas went to medical school at Syracuse University and was assigned to the Pittman Center Methodist Mission in East Tennessee.

Notoriously suspicious of outsiders, the folks living in the hills and hollers of the Smoky Mountains did not always greet Dr. Thomas with open arms. “A lot of them would hold a gun on him,” writes Parton. “If my wife dies or my daughter dies, you’re going to die, too,” they would say. Thankfully, it never went beyond empty threats doled out in fear. He was, after all, the only physician in the mountains who could deliver babies, perform surgeries, provide immunizations, snip tonsils, and treat all kinds of illnesses. Dr. Thomas was a certifiable blessing.

He did not have a lucrative medical practice and was often paid with chickens, hogs, and vegetables. On one occasion, he was paid with a cow. “I was born on January 19, and it was snowing,” writes Dolly. “When I was trying to be born, Mom was having trouble so Daddy had to ride his horse out to Pittman to get Dr. Thomas to ride with him back to our place.” With no money, the Parton family famously paid the doctor with a sack of cornmeal.

Dolly never forgot the open-hearted ministry of Dr. Thomas. In her song, she called him a “mighty, mighty man [who] enriched the lives of everyone that ever knew him … a man the Lord must have appointed to live among us mountain folks in eastern Tennessee.”

In addition to his medical ministry, Dr. Thomas also pastored a congregation. “I still remember that antiseptic smell in his little clinic by the church,” she writes in Songteller. “He was there to save those poor people of the mountains, and he was kind of a savior to us.”

Traveling the rugged terrain by foot, jeep, and horseback, Thomas is said to have made as many as 1,000 house calls each year. In her tribute song, Parton declares:

They say a man is judged by the deeds he does while livin’/

A judgment when he stands before the Lord/

And I know heaven holds a place for men like Dr. Thomas/

And I know that he’ll receive his just reward.

Despite the many challenges and hardships she faced growing up, Dolly Parton has always appeared as a joyous and generous whirlwind of gratitude. She has always counted her many blessings.

If you visit Dollywood, her theme park in Tennessee, you will see the beautiful chapel on the premises named after Dr. Thomas. It hosts services every Sunday that the park is open. Dolly actually serves as the honorary chairperson of The Dr. Robert F. Thomas Foundation, a not-for-profit charitable organization to improve the health care services available in Sevier County.

Inside the chapel, a letter from Dolly hangs on the wall: “Dr. Thomas was a man of varied talents, a man of infinite love and compassion, abundant energy, contagious enthusiasm, genuine humility and great vision, a friend, a neighbor, counsellor, minister and doctor to the people of Sevier County for over 50 years. His dream was to put an end to pain and suffering….”

Dr. Thomas lived a life of selfless service. In response, Dolly’s gratefulness for his ministry is heartfelt and extravagant. Even if we do have to be apart for this holiday, maybe words and gestures of gratitude to those we love and appreciate can help salvage a socially-distanced Thanksgiving.

Steve Beard is the curator of Thunderstruck.

My grandparents, Luther and Ada Flynn, served as missionaries at Pittman Center for 17 years. Grandad was the principal of the mission school. Pittman Center made a huge difference in the lives of many mountain people.