The Devil’s Music: How Christians Inspired, Condemned, and Embraced Rock ‘n’ Roll by Randall Stephens is a must-read for those who dig the connection between faith and pop culture.

“Much of what animates evangelical churches in the twenty-first century,” maintains Randall Stephens, “comes directly from the unlikely fusion of pentecostal religion, conservative politics, and rock and pop music.”

“The only thing that would make this book better is if it actually played the music,” writes Professor John Turner in a book review. “Stephens makes the history of American evangelicalism fun again. But you really can’t go wrong in a book centered around Elvis, Jerry Lewis, Little Richard, and Larry Norman. There are heroes and anti-heroes, troubled souls and those troubled by those troubled souls.”

“The Devil’s Music is full of spot-on observations about its subject matter,” Turner writes. “While Stephens is not the first to notice the pentecostal origins of rock ‘n’ roll, he devotes sustained attention to the importance of Pentecostalism in this story.”

“The sensuality and driving rhythm of rock ‘n’ roll owed much to outsider pentecostal church worship,” Stephens explains. Pentecostal “churches tended to welcome revved-up music and instrumental innovations,” he adds.

“Rock musicians and Penetcostals were both known for the babel of unintelligible sounds, though the enlightened could understand everything perfectly clearly,” Turner writes. “Jerry Lee Lewis (and his cousin, Jimmy Swaggart), Elvis, Johnny Cash, James Brown, and Little Richard all had Pentecostal roots, some deeper than others.” To read Turner’s complete article, click HERE.

Eric C. Miller does a worthwhile interview with Stephens, particularly when asking about why Christians were so quick to demonize—and racialize—rock?

“Well, they demonized it, in many cases, because of what they saw as a sort of sinful appropriation,” Stephens responded. “Black and white Christians accused Ray Charles of blasphemy because of how he was secularizing sacred music. Blues legend Big Bill Broonzy certainly believed Charles had gone too far. A former pastor in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, Broonzy claimed that Charles had ‘got the blues,’ but ‘he’s cryin’ sanctified. He’s mixing the blues with the spirituals.’ Or, as the critic Hollie West said about Aretha Franklin, whereas she ‘once said Jesus, she now cries baby. She hums and moans with the transfixed ecstasy of a church sister who’s experiencing the Holy Ghost.'”

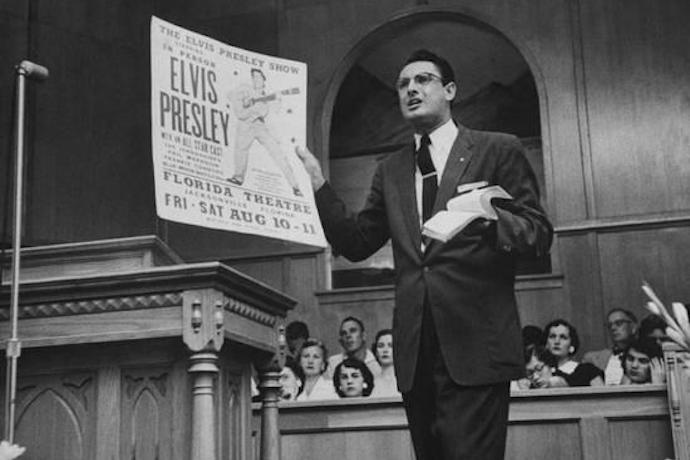

Stephens went on to say, “There were some white Pentecostals who thought that rock and rollers were thieving from church music. One of these, the Pentecostal youth pastor and author of the Cross and the Switchblade, David Wilkerson, called it ‘Satan’s Pentecost’ and portrayed rock ‘n’ roll concerts as a kind of inverted Pentecostal worship, with demonic speaking in tongues. A lot of this was in the vivid imagination of believers, of course, but it shows that, for many of these observers, there was a thin but important line that was being crossed. In the 1950s, white and black conservative Christians worried that even their church music was becoming too “worldly” or too vulgar.”

Regarding race, Stephens looked at the “white Southern Baptist Convention, Southern Presbyterians, and Southern Pentecostals, and found that their reaction to rock was almost uniformly negative and very often racialized. They attacked rock as ‘jungle music,’ ‘congo rhythms,’ and ‘savagery.'”

“In some cases this is ironic,” Stephens points out, “because these are some of the very things that Pentecostals were criticized for themselves—for race mixing and having “debased” music in their services, whether that be Hillbilly, boogie-woogie, or some kind of hybrid black and white styles. So there were all of these interesting, and specific, interconnections that I thought deserved more attention.”

Read full interview HERE.