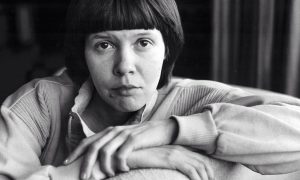

Russian dissident poet and novelist Irina Ratushinskaya, known for writing poems in her bars of soap and then memorizing them while she was in a Soviet prison camp, died in Moscow on July 5, 2017, at the age of 63. There are many fine obituaries of this courageous woman, but what follows is one of the best profiles of her indomitable spirit.

By Kathy Keay (Third Way, November 1990)

Irina Ratushinskaya was sent to a Soviet hard-labor camp in April 1983. She was beaten, force-fed, put in solitary confinement in brutal, freezing conditions, and became so gravely ill that many feared she would not survive. Her “crime” – writing poetry. For this, she was branded “a dangerous state criminal” and was sentenced a second time to seven years hard labor and five years internal exile – the maximum possible punishment for this offense and the hardest on any woman since the Stalin era.

Irina was the youngest woman in the Small Zone – a special unit for women political prisoners at Barashevo in Mordovia. She repeatedly protested against camp practices which flouted Soviet as well as international law. In May 1986 her first book of poems, No I am Not Afraid, was published in the UK. Her plight, by now a matter for world public concern, finally led to her release on October 9. Two months later she was allowed to come to Britain.

What was it about this 28-year-old woman which so enraged the Soviet authorities? How did she survive such grueling conditions? What legacy does she leave through her poems?

Uncompromising truth. A poet’s calling is to speak the truth. In Irina’s words, “… to call things by their real names.” Russian writers are not the only ones to believe that, but since the 1917 Revolution those who share this conviction have certainly paid for it. When Irina was arrested one of her friends commented, “This is a tragedy, not only for us her friends but also for Russian poetry. A poet with a vision of the world that is startling, unique in its tenacity and its penetration of colors and sounds is behind bars.” The same happened to other Russian poets: Gumilyov, Mandclstam, Brodsky and Natalya Gorbanevskaya. “For more than sixty years our poetry has been shot in the back in this fashion. What can you say about a government that is forced to kill poets in order to maintain law and order? It is like breaking a watch – a falsification of time, for poetry is nothing other than re-constructed time.” It will outlive the creation of the state which tries to destroy it and its dissemination transcends the boundaries of space and time laid down by the state. This is why the genuine poet is feared and hated. She will not surrender herself or her art to what is false, or to any totalitarian regime or political ideology.

Poems of the soul. To any serious writer, the freedom to write what you like is vital. Irina maintains that no one should stand between a writer and a clean sheet of paper. “No one should be able to search my writer’s table.” When these freedoms are violated, the writer herself is violated, though usually not defeated.

When this happened to Irina, she commented, “The only place they couldn’t search was my brain and my husband’s brain.” Her husband Igor agrees: “Poems are created in the soul, not on paper.” Irina learned all her poems by heart, wrote them down on tiny pieces of paper which miraculously were brought to the West in smuggled samidzat copies, cassette tape recordings, and memorized versions, and later published.

Prophetic verse. To hear Irina Ratushinskaya reading her poetry is a tremendously moving experience. This woman, once beaten unconscious for such writing; dragged along a corridor and dumped on the concrete floor by her cell, stands tall and dignified before her audience. She reads her own prophetic verse with disturbing clarity and (surprisingly perhaps) no sign of bitterness or hysteria.

“I will live and survive and be asked: / How they slammed my head against a trestle. / How I had to freeze at nights, / How my hair started to turn grey…”

At the end of almost every poem she raises her head and waits for the inevitable question: How did you do it?

Great discovery. There is no simple answer to this question, although it is evident that from birth Irina, like a number of Russian writers before her, found the psychology of the Soviet system entirely unacceptable. Every attempt, whether by her parents or by school, to make her into a “builder of communism” led to conflict.

Irina started to believe in God at an early age, embracing the Catholic faith of her Polish grandparents. According to Igor, it was this faith which formed and was to preserve her soul. Although she loved literature and art, she chose not to specialize in these subjects at university, since in the Soviet Union, as everywhere else, such disciplines involve discussing ideological concepts. This would have been too risky for Irina, who would have constantly clashed with the authorities, so she opted to study natural science.

While at university she experimented with writing light humorous scripts and a few poems, but didn’t begin to write in earnest until the late seventies when she discovered the poetry of the Russian Silver Age and the great “quartet” of Russian poets: Akhmatova, Mandelstam, Pasternak, and Tavetayeva. Their works, hard to obtain in the USSR, had been circulating unofficially among the students. For Irina, this discovery was an intense spiritual experience, after which she began to write her own poems with greater seriousness and a sense of artistic commitment.

The first beauty in captivity. In spite of being accused of undermining the state, Irina’s poems have never called directly for the overthrow of the Soviet regime. To read them is to enter a world which is quite remote from politics. A world where she makes friends with spiders, dreams – among other things – of the luxury of wearing a red velvet dress, where she notices a frost-covered window which she describes as “the first beauty” she saw in captivity. It was this ability to appreciate even the smallest sign of beauty which helped her to survive when there were neither letters nor any news from loved ones. It was this which she chose to remember.

“No spyholes or walls. / Nor cell-bars, nor the long-endured pain – / Only a blue radiance on a tiny pane of glass. Such a gift can only be received once / And perhaps is only needed once.”

The stuff that dreams are made of. The ability to spot beauty, absorb it and to feed the soul within the imagination are not always valued, even within the “free world.” Political necessity, the Protestant work ethic, or simply the tyranny of the urgent, too often claim people’s best energies and leave little room for the spirit to breathe and the soul to expand. Yet as Irina asserts her “childish, flouted right to beauty,” as she feasts in her mind upon the inaccessible, she is doing something which is entirely natural, although its effects are also transcendent.

In her poem, “Some people’s dreams pay all their bills,” she writes: “My day is like a donkey, bridled, laden, / My night deserted, like the prison light, / But in my soul – it’s no good, I am guilty: / I keep on sowing it, and in my mind I make / The thousandth stitch, as I do up my anorak / And try on my tarpaulin boots.” What Solzhenitsyn portrayed through One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Irina lives through in her poetry. Like many prisoners, she discovered that the greatest thing to be feared is not the interrogators but the devils running around in your own heart; the capacity to hate which so easily flourishes under tortuous circumstances.

“You must not hate,” she says. “I only understood this in labor camp. To decide not to hate is not just to have mercy on your interrogators but also on yourself.’ But how can you just decide not to hate? Some under similar conditions have cursed God and taken their own lives – at least recited Bible verses; the Lord’s Prayer – anything to help them ‘overcome evil with good.’” Irina called repeatedly upon her God-given imagination. “I would think of the interrogators as people,” she recalls, “as fathers with children and I would imagine their children playing with my children. And I would pity them, because I believed one day I would be out of this awful camp, but they might be stuck here for the rest of their lives. This is how I would prevent myself from hating. And to see the funny side of things – that instantly kills hatred.”

Certainly there is a sense of “Father forgive them for they know not what they do” in Irina’s poems, though it is coupled with an uncompromising exposure of the evils which they perpetrate and the dehumanizing effects they have upon their victims.

Songs of solidarity. Solitary confinement recognizes that the individual who is isolated usually becomes vulnerable quite quickly and that prisoners who are left to survive together gain a certain strength. This is not always the case but it was undoubtedly so for Irina and the women in the Small Zone. Putting all the troublemakers into one camp, the authorities unwittingly created a community of women who helped sustain one another with courageous and sacrificial mutual support. They stubbornly resisted all the infringements of penal regulations perpetuated by the camp guards. In her poems, Irina describes these women as “the best people in all the earth; the most tender and also the most invincible.”

Perhaps it was not without significance that many shared a common faith; among them Russian Orthodox, Pentecostal, Baptists and others. Unlike in the “free world,” this was no problem, rather an excuse for as many celebrations as possible. “We all had different traditions, so we celebrated Christmas and Easter over and over again.” There was always a saint’s day or some other point in the Christian calendar to celebrate. “Altogether we were the most happy family,” she recalls. The unquenchable spirit of these women was contagious.

The hand on the shoulder. Irina recalls how many of the agnostics within the camp came to believe in God. This was not first and foremost an intellectual decision. “When you don’t own even your own body, you come to understand that you do own your own soul, and that it is better to let the body die than to lose your own personality, your own soul.”

Long before glasnost these women played an important role in the struggle for human rights and for the existence of separate nationalities within the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. “We got the necessary support,” says Irina. In her poems she describes it as “the hand on the shoulder”– the invisible sign of God’s presence when it was needed most.

The real world. Irina’s experience overcomes fear in the face of life threatened. In this way also, she has a great deal to pass on to others who, for whatever reason, experience life as being threatened. Her poems are not neurotic nor vengeful (in contrast, one feels, to some of the Psalms). They are full of life, detail and uncompromising honesty. They are spiritual in the truest sense because they are rooted in the harsh realities of the present, yet point to a different reality not so far away. During her time in the Small Zone she had an unmistakable awareness that the real world is, in its fullest sense, beyond this little world. “Being close to death you can feel there’s something beyond. This is not wishful thinking; it appears to be a strong conviction which energizes her when everything is still grey and apparently hopeless.

“And here I go flying down the steps – / Almost somersaults – as in a dream / Oh! how urgently I need to go there / Where it’s bluer than blue – / To splash in the puddles by the faucet / to frighten the pigeons away from the caves.”

The material world. Since her release, Irina remarks how the hand on the shoulder seems less noticeable, less firm than when she was in prison. “When I was released, I felt happiness all around me, but I was surprisingly lonely.” She acknowledges that it would be difficult to say which is the better environment in which to write poetry – the West, where people have enough to eat, or the concentration camp, where everyone goes hungry. She recognizes that when people seems to have everything they need in material terms it is easy to lose or not to recognize any sense of God. For the individual, this can lead to an increasing sense of loss of direction and spiritual poverty.

And for poetry? A rather egocentric playing around with words.

Does this explain what has happened to so much poetry in the “free West”? Certainly many of our poets don’t seem to have a prophetic role. Often the poet becomes a jester, a celebrated cynic, whose talent is at worst employed in entertaining people at the expense of others. Has the poet no responsibility in respect of Truth?

Crown of thorn. We can be grateful for the voice of Irina Ratushinskaya and for others like her. As well as being a remarkably talented poet, she has been described as hearing “historical and absolute time with equal precision.” In this sense, she is able to discern Truth and remains a prophet in our midst. She reminds us that many of the real heroes and heroines in Russia are still behind bars. They have been fighting for democracy long before Gorbachev; they are the prisoners of glasnost who are still not free.

And herself? Her experience exposes the folly of a state which has repeatedly tried to quench the Spirit; which, according to Joseph Brodsky, ignores the fact that “a crown of thorns on the head of a bard has a way of turning into a laurel.” This shows that the very conviction of a poet is not only a criminal offense but a spiritual one. It serves as a warning that, even towards the end of the second millennium after the birth of Christ, the conviction of a 20-year old woman for making and distributing poems is a severe indictment not only of the first socialist state in living history, but of any other group or regime, political or religious, which is foolish enough to try and silence its dissident voices. If they are concerned with Truth and alive to the Spirit, they have a way of resurrecting themselves in the most unpredictable ways and the most unexpected places.

“I shall write about all the sad people / Who have remained on the shore. / About those who have been condemned / to silence / I shall write. / Then burn what I have written. / Oh, how these lines will soar ….”

Kathy Keay wrote this for Third Way Magazine in November 1990. Poems quoted were used with the permission of Bloodaxe books, the publishers of No I am not Afraid and Family Letters by Irina Ratushinskaya.

Beautiful obituary. Thank you.