By Steve Beard

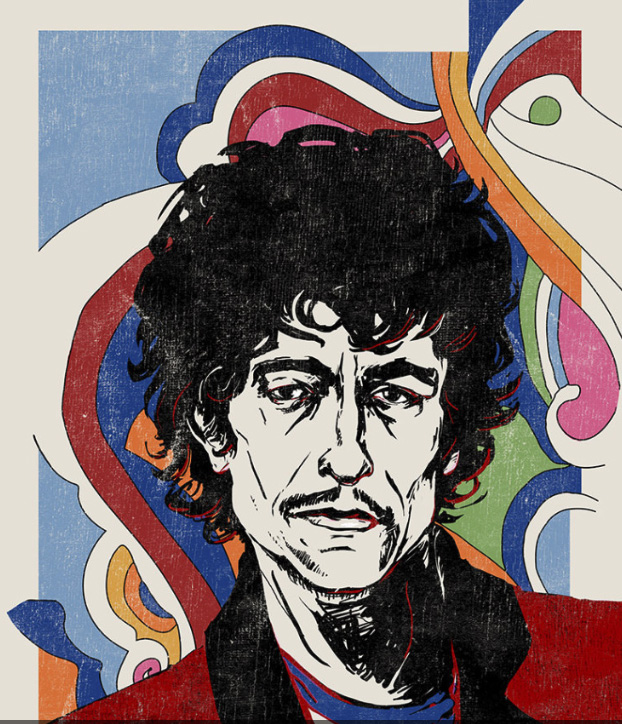

Shooting just began in Montreal for I’m Not There, the new biopic of Bob Dylan. In the wake of successful films about musicians, this one promises to definitely be different than Ray or Walk the Line. Six different actors will play various incarnations of Dylan’s personality: Heath Ledger, Christian Bale, Cate Blanchett, Richard Gere, Ben Whishaw, and Marcus Carl Franklin. As you may know, Blanchett is female and Franklin is black.

That kind of Dylanesque maneuver has got to have the nasally folk icon smirking.

For more than forty years, Dylan has energized the anti-war and civil rights movements, excited poets and songwriters, and exasperated those who have attempted to neatly pinpoint his philosophy on love, life, death, and the Almighty. With I’m Not There, director Todd Haynes will get his shot at defining Dylan.

There seems to be no end to the fascination with the man who is arguably America’s most significant and mysterious troubadour. Fans snatched up his autobiographical Chronicles, Vol. 1. PBS recently aired No Direction Home, Martin Scorsese’s four-hour documentary on Dylan’s life from 1961 to 1966. The Dylan musical, “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” will open on Broadway in October. All the while, he keeps doing his thing. The recently released Modern Times is Dylan’s 44th album.

Yet even with the flood of content from and about Dylan, fans and observers still find themselves thirsting to know more; to unwrap the enigma and comprehend the reluctant prophet. “All I’d ever done was sing songs that were dead straight and expressed powerful new realities,” he writes in Chronicles. “I had very little in common with and knew even less about a generation that I was supposed to be the voice of.”

Dylan has a nagging habit of pointing observers to his songs for answers about his beliefs. As illustrated in the new 440-page Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews, however, there have been times when he has been more forthright. “I’ve always thought there was a superior power, that this is not the real world and that there’s a world to come,” he told Kurt Loder in a 1984 Rolling Stone interview. “That no soul has died, every soul is alive, either in holiness or in flames. And there’s probably a lot of middle ground.”

Of course, that response was given in the wake of his trilogy of gospel-related albums he produced after becoming a Christian in 1978—one of the most controversial conversions of the modern era. But his philosophy about life, death, and the immortality of the soul were not new subjects for him. When he was interviewed by Nat Hentoff for Playboy in 1966, it was noted that Dylan had said that he had done “everything I ever wanted to do.” If that was the case, Hentoff asked, what did he have to look forward to? Dylan deadpanned, “Salvation. Just plain salvation.” Anything else? Dylan continued, “Praying. I’d also like to start a cookbook magazine…I want to referee a heavyweight championship fight.”

Dylan was not being flippant, he was just being honest.

His public proclamations about Jesus brought far more controversy to his career than when he was booed for playing an electric guitar instead of an acoustic at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965. His spiritual quest was exceedingly more countercultural than a mere shift of musical instruments. Dylan’s gospel albums dumbfounded critics and aggravated a segment of his fan base when the “spokesman for a generation” had become a preacher.

Yet plenty of people heard the art that Dylan was creating. Songwriter Leonard Cohen once referred to Dylan as “the Picasso of song.” He recalls, “People came to me when he put out [Slow Train Coming] and said, ‘This guy’s finished. He can’t speak to us anymore.’ I thought those were some of the most beautiful gospel songs that have ever entered the whole landscape of gospel music.”

Bono agrees. “This album was such a breakthrough,” the U2 singer recalls. “I was always annoyed that rock could cover any taboo—sexual, cultural, political—but nobody could be upfront about their spiritual life. Before Bob Dylan, no white people could sing about God. He opened me to these possibilities.”

Dylanologists on the Internet will continue to debate the state of his theological orientation. Dylan, however, will point them right back to his art. “Those old songs are my lexicon and my prayer book,” he told The New York Times in 1997. “All my beliefs come out of those old songs, literally, anything from ‘Let Me Rest on That Peaceful Mountain’ to ‘Keep on the Sunny Side.’ You can find all my philosophy in those old songs. I believe in a God of time and space, but if people ask me about that, my impulse is to point them back toward those songs. I believe in Hank Williams singing ‘I Saw the Light.’ I’ve seen the light, too.”

A few years ago, Dylan was making a habit of opening his concerts with the song “I Am the Man, Thomas.” Out of the more than 500 songs he wrote, it would not have been unreasonable to ask why he was opening with a cover tune from the old Stanley Brothers.

The song is about a conversation between Jesus Christ and the man that all Sunday school alumni know as Doubting Thomas. “Look at these nail scars here in my hands/ They pierced me in the side, Thomas, I am the Man/ They made me bear the cross, Thomas, I am the Man/ They laid me in the tomb, Thomas, I am the Man/ In three days I arose, Thomas, I am the Man.”

It would only be offering mere speculation as to why Dylan includes his gospel-centric songs such as “Man of Peace,” “In the Garden,” or “I Believe in You” on his playlist. Perhaps we should be content to conclude that he has always been an intriguing wordsmith on a quest to find God and is merely continuing that journey.

Bob Dylan never liked being a prophet or a preacher. His is a more artistic disposition. Once, while being interviewed in London, he began to talk about the kind of people he admired. He spoke of a doctor or surgeon—someone who “can save somebody’s life on the highway. I mean, that’s a man I’m gonna look up to, as being somebody with some talent.” Dylan went on to say, “Not to say, though, that art is valueless. I think art can lead you to God.” Asked if that was art’s purpose, he remarked, “I think so. I think that’s everything’s purpose. I mean, if it’s not doing that, it’s leading you the other way. It’s certainly not leading you nowhere.”

If anyone would know something like that about art, it would definitely be Bob Dylan.

Steve Beard is the creator and editor of Thunderstruck Media.