-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- Happy Birthday Brian Setzer! | on Stray Cat Patron Saint: Brian Setzer leans on St. Jude

- Happy Birthday Brian Setzer! | on Guitar Slinger: Brian Setzer

- Joe on Crucifixes, Guthrie, and the Dropkick Murphys

- Richard L Anderson on ARCHIVES: The Royal Faith of Queen Elizabeth

- Raquel Welch became a faithful Presbyterian? — GetReligion - South Dakota Digital News on Not Just Another Pretty Face: Raquel Welch, RIP

Archives

- February 2024

- December 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- January 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- October 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- July 2012

- January 2008

- December 2007

- September 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- September 2005

- September 2004

- January 2004

- December 2003

- September 2003

- May 2003

- January 2003

- December 2002

- September 2002

- January 2002

- September 1992

Categories

Happy Valentine’s Day 2

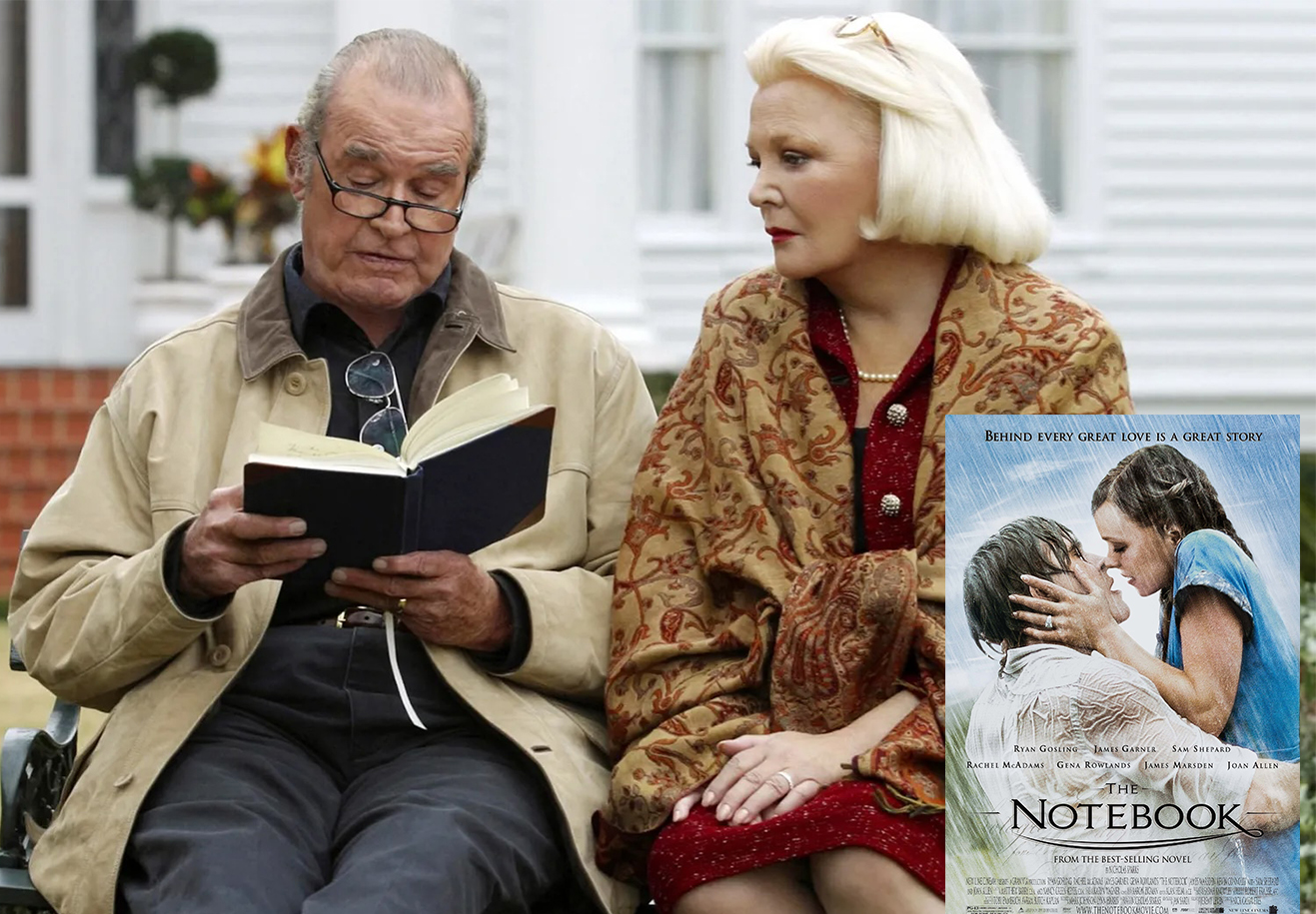

“The Notebook” portrays a steamy 1940s summer romance between Rachel McAdams and Ryan Gosling. He senses the destiny of a lifetime together. She thinks he’s crazy. Nevertheless, she is wooed by his charm. It is red-hot teenage infatuation that peels the paint — that is, until family meddling and World War II tear the young couple asunder.

In the film, the fairy tale romance is read aloud each day by a man (James Garner) who comes to visit an Alzheimer’s patient (Gena Rowlands) in a nursing home (thus the photo). Each visit reveals more of the combustible love story as he faithfully reads to her each day. We see the way that she engages the story as if it was familiar, battling the ruthless effects of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Whether you’re a Sparks fan or not, the movie was about enduring and passionate love that burns brightly with flames at the outset and ends up graduating to white-hot coals that last a lifetime. There is an everlastingness about it, a certain mysticism, an unmistakable magnetism, and an undying attraction that carries on to the exit gate of life.

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Happy Valentine’s Day 1

I’ve been to the Rev. Al Green’s church in Memphis three times – right down the road from Graceland. When he starts bobbing and weaving in the pulpit, I can’t help but hear the Soul Man singing, “Let’s, let’s stay together/ Lovin’ you whether, whether/ Times are good or bad, happy or sad.” In my mind, he will always be the funky St. Valentine.

Before the greeting card companies began milking it, February 14 was the feast of the martyred Saint Valentine from the third century. According to tradition, the skull of the patron saint of lovers – beheaded because he secretly married couples during the reign of Roman Emperor Gothicus – supposedly is encased at the Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin, Italy (thus the photo on this Ash Wednesday).

I simply adore the visual because – and I say this with all due respect – sometimes it just seems like you lose your head (or at least your mind) when you fall in love.

Yep, I am well aware of the complicated history of whether there was one or two Saint Valentines and where exactly all his (their) relics ended up. While that is troubling to some, I rather enjoy the inexactitude of Saint Valentine’s story.

Love is kinda sloppy and messy like that – and complicated. It reminds me of one of my favorite love songs, “The Golden State,” by John Doe of X. “You are the hole in my head/ I am the pain in your neck/ You are the lump in my throat/ I am the aching in your heart.” Been there, done that. And I don’t regret it for a moment.

To those in the throes of love, Congratulations. Muah. Muah. Muah. So happy for you. Honestly. Allow me to leave you with this irrationally beautiful sentiment on love from songwriter Nick Cave. I can see him saying this to his lovely wife Susie:

“Come sail your ships around me/ And burn your bridges down/ We make a little history, baby/ Every time you come around. Come loose your dogs upon me/ And let your hair hang down/ You are a little mystery to me/ Every time you come around.”

I love that Valentine sentiment. Sail your ship around the one you love. Let your hair hang down. Toast to the mystery of the heart. Hold hands, squeeze tight, be grateful. Happy Valentine’s Day!

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Tomorrow is Valentine’s Day

Friendly reminder that tomorrow is Valentine’s Day. If you have – God forbid — forgotten to get a sweet treat for your sweet treat, you still have time. Don’t get caught on thin ice. Scurry off and get snacks or diamonds – like, right now! Meanwhile, enjoy one of my fave depictions of St. Valentine by Italian artist Paolo Consorti. Ironically, this memorably imaginary portrayal of the patron saint of love smelling roses on ice skates was discovered in a small sanctuary by my friend Sister Rose Pacatte while she was participating in a film festival in Italy. The (contested relics) of St. Valentine are actually at the Basilica and the Carmelite Monastery Church in Terni, an hour north of Rome. Spread the love.

Friendly reminder that tomorrow is Valentine’s Day. If you have – God forbid — forgotten to get a sweet treat for your sweet treat, you still have time. Don’t get caught on thin ice. Scurry off and get snacks or diamonds – like, right now! Meanwhile, enjoy one of my fave depictions of St. Valentine by Italian artist Paolo Consorti. Ironically, this memorably imaginary portrayal of the patron saint of love smelling roses on ice skates was discovered in a small sanctuary by my friend Sister Rose Pacatte while she was participating in a film festival in Italy. The (contested relics) of St. Valentine are actually at the Basilica and the Carmelite Monastery Church in Terni, an hour north of Rome. Spread the love.

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Remembering her birthday: Joann Beard, RIP

February 9 is my mom’s birthday. It’s kinda been a rough morning. Still mourning, I guess. My family misses her.

February 9 is my mom’s birthday. It’s kinda been a rough morning. Still mourning, I guess. My family misses her.

My mom’s death certificate states August 30, 2023. It’s wrong. I was there. Actually, death came seven minutes before midnight, August 29. The nurse sent from the mortuary to fill out the paperwork showed up at my parents’ home several hours after Mom “shed her mortal coil,” as the poets would put it. August 30 was fine for filling out the form. It was just seven minutes off. In the provocative scheme of eternity, the paperwork was no big deal.

Eighty years. That’s what my mom, Joann Beard, was given to soak up the joy and anguish of life. She fought for every moment. My family was grateful. We miss her.

First thing this morning, I listened to a song from Blind Gary Davis (1896-1972), a minister and blues artist. “Well now death don’t have no mercy in this land/ He’ll come to your house and he won’t stay long/ Look ’round the room one of your family will be gone/ Death don’t have no mercy in this land.”

Death may, indeed, not have mercy – but joy and comfort are found in friends and family in the shadow of death. In my faith tradition, death does not have the final word.

Continue reading

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Happy St. Brigid Day!

By Steve Beard

In Ireland, the first day of February is St. Brigid’s Day, as well as the ancient Celtic festival of Imbolc, marking new birth and the threshold of spring. Not long ago, it was christened as an Irish government holiday (St. Patrick’s Day became an Irish “bank holiday” in 1903). The occasion is a celebration for both Christians and those who observe pre-Christian Gaelic traditions.

Today marks 1,500 years since St. Brigid’s death.

During a recent trip to Ireland, I was mesmerized by a compelling mural depicting a dual-faced Brigid in the town of Dundalk – halfway between Belfast and Dublin on Ireland’s east coast. After returning home, I read the medieval hagiography of this intriguing woman who died almost 1,500 years ago.

St. Brigid is said to be the child of a pagan chieftain and a Christian slave woman. It is thought that her father named his daughter after Brigid, the indigenous Celtic goddess associated with spring, healing, fire, fertility, and poetry. As a girl, she is said to have been raised in a separate Druid home before becoming a Christian at a young age.

The two-story mural (above) created by the artist Friz in Dundalk attempts to portray the similar-but-different stories told about both Brigids. Because of the time period, there are many details that we do not know. Scholars continue to debate the competitive portrayals of the saintly abbess and the Gaelic goddess.

What has been passed down is that Saint Brigid (451-525) was a winsome and compassionate founder of one of Ireland’s most important and remarkable dual monasteries for both nuns and monks. Although exact dates are debated, St. Brigid’s ministry would have taken place after St. Patrick’s death in 461. The Abbey at Kildare – 40 miles west of Dublin – is thought to be built upon the very site of a shrine to Brigid the goddess under a large oak tree (Cill Dara, “church of the oak”).

The Abbey was known for its Christian hospitality, as well as its emphasis on art, metalwork, and “illuminated manuscripts” similar to the world-renowned Book of Kells. Unfortunately, the Book of Kildare is lost to history, and the Abbey at Kildare was destroyed in the 12th century (the Cathedral of Kildare is now built on the original site).

“This woman … grew in exceptional virtues and by the fame of her good deeds drew to herself from all the provinces of Ireland inestimable number of people of both sexes…” wrote Cogitosus (c. 650), a monk of Kildare, in his remembrance of St. Brigid. “On the firm foundation of faith she established her monastery … which is the head of almost all the churches of Ireland and holds the place of honor among all the monasteries of the Irish. Its jurisdiction extends over the whole of the land of Ireland, from coast to coast.” (Cogitosus’ work is the earliest hagiography found in Ireland.)

Because of her prominence, St. Brigid is also one of the three patron saints of Ireland, alongside St. Patrick and St. Columba.

There are numerous stories of her faith and tenderheartedness. As a child, she gave away butter and bacon to those who were hungry (including a whimpering dog). She is said to have also given away her father’s jewel-encrusted sword to a beggar in need – much to her father’s exasperation. After trying to sell her off, he finally realized that allowing her to live a life devoted to her faith made far more sense.

![]() There are innumerable churches, schools, athletic associations, and more than a dozen holy wells in Ireland dedicated to St. Brigid. However, she is most well-known for weaving a cross from straw or reeds while at the deathbed of a pagan chieftain who had grown delirious with his illness. As she sat with him, she weaved a cross and explained its meaning. In some versions of the story, it is said that it brought peace to the man’s heart and he sought baptism before his final breath. (Modern day Irish children celebrate St. Brigid’s feast by weaving crosses from reeds. For the icon, click HERE.)

There are innumerable churches, schools, athletic associations, and more than a dozen holy wells in Ireland dedicated to St. Brigid. However, she is most well-known for weaving a cross from straw or reeds while at the deathbed of a pagan chieftain who had grown delirious with his illness. As she sat with him, she weaved a cross and explained its meaning. In some versions of the story, it is said that it brought peace to the man’s heart and he sought baptism before his final breath. (Modern day Irish children celebrate St. Brigid’s feast by weaving crosses from reeds. For the icon, click HERE.)

In his remembrance of her kindness, generosity, and miraculous life, Cogitosus did not fail to mention the time Brigid turned bathwater into beer. “On another extraordinary occasion some lepers asked this venerable Brigid for some beer, but she did not have any beer to give them,” he wrote. “Seeing water that had been prepared for baths, she blessed it in the strength of her faith and turned it into the very best beer, which she generously dispensed to the thirsty.”

Notably, the legacy of St. Brigid is immortalized outside her native Ireland. There are, for example, Brigidine nuns at work all over the globe. One of St. Brigid’s tunics is said to be treasured at the Cathedral of Bruges, Belgium. She is the patron saint of the oldest church in London – St. Bride’s, Fleet Street. There is even a Chiesa di Santa Brigida d’Irlanda (Church of St. Brigid of Ireland) in Piacenza, Italy. Twenty churches or parishes are named after her in the United States.

In the thirteenth century, three Irish knights took the skull of St. Brigid with them on a journey to the Holy Land as a sacred relic. It is said that the knights did battle in Portugal and stayed with her revered remains until their deaths. The three knights are interred in the tombs of St. Brigid’s chapel within the Church of St. John outside of Lisbon.

“Brigid bridges the greatest divide, between heaven and earth, between God and humanity,” wrote religious scholar Maeve Brigid Callan recently in The Irish Times. “The sixth- or seventh-century priest/poet Broccán describes her as ‘a marvelous ladder for pagans to visit the kingdom of Mary’s Son.’ From childhood on, she simultaneously embodied the highest Christian and indigenous Irish ideals, integrating attributes exemplified both by Christ at Cana and the Sea of Galilee and by native goddesses of fertility and sovereignty.”

The religious community that she helped create in Kildare, Ireland, centuries ago was a true sanctuary for weary souls. “The city is a great metropolis within whose borders, which St. Brigid marked out as a clear boundary, no earthly enemy nor hostile attack is to be feared,” wrote Cogitosus. “For the city is the safest place of refuge of all the towns anywhere in the whole of Ireland, with all its fugitives. …

“And who could count the various multitudes and innumerable crowds of people who swarm here from all provinces. Some come for the abundance of the festivals, some to have their illnesses cured, some come to see the spectacle of the crowds, and others come with great gifts for the feast of St. Brigid, who fell asleep on the first of February, safely casting off the burden of the flesh, and followed the Lamb into the heavenly mansions.”

Happy St. Brigid’s Day!

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Rick Rubin on taking communion with Johnny Cash and not rushing creativity

NPR, December 10, 2023

EXCERPT

Rachel Martin: Your book, The Creative Act, reads as sort of a spiritual text. Do you have a spiritual architecture to your own life?

Rachel Martin: Your book, The Creative Act, reads as sort of a spiritual text. Do you have a spiritual architecture to your own life?

Rick Rubin: I will say I’m a seeker. So I read across the board, different practices. I’m looking at a bunch of books in front of me now. If you could see the books, you’d really laugh.

Martin: Tell me what they are!

Rubin: OK, so there’s Wherever You Go, There You Are, which is a Jon Kabat-Zinn book on meditation. Below that is I Am That by Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj. Below that is Awakening the Third Eye. There’s a book called 101 Things I Learned in Architecture School. There’s a book called Entering the Tao.

Martin: Alright, you’ve made your point. [laughs] You’re a reader, and a seeker. Those are all of a piece, for sure. I mean, a seeker is a thing that’s sort of, not to push back on you, but it’s an easy answer. Lots of people are seekers. Do you believe in God?

Rubin: Yes.

Martin: You do?

Rubin: Yes, yes, yes. Yes. I have a knowingness that there is a power greater than us that seems to animate everything. That’s how I would describe it. However this system works, this world that we’re in, this universe that we’re in, however it works, I don’t think it’s accidental.

I feel like there’s some creative energy behind it. We have help. When we’re making something beautiful, we have help. We’re not working alone.

Martin: I read that when you were producing Johnny Cash, near the end of his life, with his last albums, that you took communion with him. That was something that was important to him and you were enthusiastic about it.

Rubin: From the time he got sick, we did it every day. I said, “I’ve never done communion.” And he’s like, “Oh, it’s a beautiful practice. Let’s do it together.” And then we did it together in person the first time. And then I said, “Well, while you’re sick, should we just continue doing it every day?” And he’s like, “Great, let’s do it.” Continue reading

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Shane MacGowan RIP

The funeral of Shane MacGowan, frontman of The Pogues, was held December 8 at the Saint Mary of the Rosary Church in the small town of Nenagh in County Tipperary – 100 miles west from Dublin. The beloved singer died on November 30, at age 65, from complications of pneumonia. His wife and sister were by his side. Prayers and the last rites were read during his passing.

The funeral procession began earlier on the day of the funeral with a two-mile trek through the center of Dublin.

His passing was sad, but not-surprising, news to fans around the globe. Spotlighted during this season of the year, listeners are able to hear his unlikely holiday hit played on the radio. “Fairytale of New York” opens with the unforgettable lines: “It was Christmas Eve babe/In the drunk tank/An old man said to me, won’t see another one.”

Like so many other American fans, I watched his funeral online.

The church in Nenagh was filled with luminaries including Irish President Michael D. Higgins, former Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams, Game Of Thrones actor Aidan Gillen, and actor Johnny Depp (a pallbearer).

The music was spot-on. At various times in the service, Nick Cave performed “Rainy Night in Soho,” Imelda May sang “You’re the One” with Declan O’Rourke and Liam Ó Maonlaí, the Hothouse Flowers frontman. Cait O’Riordan, The Pogues bassist, and musician, John Francis Flynn delivered “I’m a Man You Don’t Meet Every Day,” recorded by the band in 1985.

An audiotape recording of Bono reading from 1 Corinthians 13:11-13 (The Message) for the occasion was played during the service. Verse 12: “We don’t yet see things clearly. We’re squinting in a fog, peering through a mist. But it won’t be long before the weather clears and the sun shines bright! We’ll see it all then, see it all as clearly as God sees us, knowing him directly just as he knows us!”

Waltzing in church. Only moments after celebrating communion, some mourners unconventionally jumped the front pew and joyfully waltzed in the church as Glen Hansard and Lisa O’Neill performed a rousing version of the 1987 hit “Fairytale of New York.” Continue reading

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

20th Anniversary: Elf rekindles the Christmas spirit

Editorial use only Mandatory Credit: Photo by REX/Shutterstock (436743s) WILL FERRELL AND DIRECTOR JOHN FAVREAU ‘ELF’ FILM – 2003 REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

By Steve Beard

2003 National Review

One of this season’s most enjoyable films is the new Christmas comedy Elf starring Will Ferrell, Ed Asner, Bob Newhart, Mary Steenburgen, Zooey Deschanel, James Caan, and directed by the talented John Favreau.

In the spirit of Christmas classics such as Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer, Frosty the Snowman, and Scrooge, Favreau has developed the kind of uproarious holiday film that is, as he says, “irreverent and edgy without being offensive.” Elf portrays the power of love to overwhelm cynicism and apathy. It also touches upon themes of redemption, charity, and the importance of family. Continue reading

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

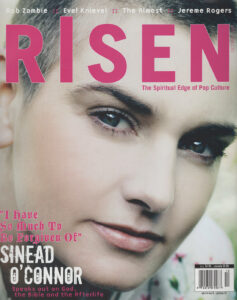

Sinead O’Connor RIP

Sinead O’Connor: A second listen

Sinead O’Connor: A second listen

2007 —

[Editor’s note: This column was written more than 10 years before Sinead O’Connor converted to Islam in 2018.]

Some of my churchgoing friends were perplexed by my recent praise of Sinead O’Connor. They still have visceral memories of a brash young woman tearing up a picture of Pope John Paul II on national television fifteen years ago.

While their reaction is understandable, I have asked them to lend her an ear. Quite literally, I have encouraged them to listen to her new double album Theology — a stunning collection of songs taken from the Old Testament books of Psalms, the Song of Solomon, and Samuel. Also on the album are covers of “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” from Jesus Christ Superstar and Curtis Mayfield’s “We the People Who Are Darker Than Blue.” Continue reading

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Sister Rosetta Tharpe: electric guitar trailblazer

Keith Richards and Eric Clapton worshipped her solos, and Elvis idolized her sound. Denny Ilett profiles the great Sister Rosette Tharpe for Guitarist.

Excerpt: Tharpe joined Lucky Millinder’s orchestra for her first recordings at the end of October 1938 waxing four sides for Decca. That’s All and My Man And I feature just Tharpe’s voice and Delta-infused National guitar. Sounding for all the world like a female Robert Johnson, Rosetta’s sparkling voice soared over her accompaniment, demonstrating her mastery of the country blues style perfectly.

The Lonesome Road – an evergreen jazz standard with a gospel-leaning lyric later recorded by the likes of Frank Sinatra and Nat King Cole – sees Rosetta performing solely as vocalist, her church-influenced yet blues-drenched voice perfect for this material.

It’s with Rock Me, however, that we hear Tharpe’s electric guitar for the first time and, significantly, this is the very record that had such a profound influence on future rock ’n’ rollers such as Elvis, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis.

The entire Guitarist article can be read HERE.

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment