By: Steve Beard

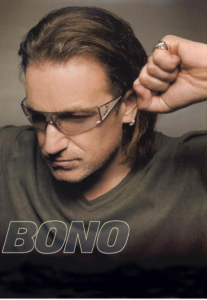

A review of Bono: In Conversation with Michka Assayas by Michka Assayas (Riverhead, 2005).

Life is a stage for Bono. The charismatic Irishman has lived under the spotlight of countless venues around the globe. His bleeding-heart social activism on behalf of the poor and suffering in Africa has landed him behind podiums next to the most powerful politicians in the world. The paparazzi are present to chronicle the overwhelmingly hip, blue-tinted sunglasses in a room of dramatically un-hip policy wonks.

Everything seems larger when it deals with Bono—the issues he addresses, the questions he ponders, and the forums he is granted. Nowhere is that more clearly displayed than in the recently published 323-page Q&A, titled Bono: In Conversation with Michka Assayas.

Everything seems larger when it deals with Bono—the issues he addresses, the questions he ponders, and the forums he is granted. Nowhere is that more clearly displayed than in the recently published 323-page Q&A, titled Bono: In Conversation with Michka Assayas.

Assayas is a French music journalist who has covered the band U2 from its inception. Over the period of two years, Bono and Assayas explored Bono’s childhood, the emergence of the band, his marriage, his social activism, the peculiar nature of celebrity, and the way he works out his Christianity. What arises as the most interesting aspect of the book is Bono’s fearless and winsome witness to faith.

At the height of his success and fame, Bono and his father would often go down to a local pub and drink Irish whiskey on Sunday afternoons. On one occasion his father told him, “There’s one thing I envy of you. I don’t envy anything else. You do seem to have a relationship with God.” Bono asked: “Didn’t you ever have one?” “No,” he said. “But you have been a Catholic for most of your life,” Bono responded. “Yeah, lots of people are Catholic. It was a one-way conversation. . . . You seem to hear something back from the silence!” Bono said: “That’s true, I do.”

“How do you feel it?” His father asked him. “I hear it in some sort of instinctive way, I feel a response to a prayer, or I feel led in a direction,” Bono replied. “Or if I’m studying the Scriptures, they become alive in an odd way, and they make sense to the moment I’m in, they’re no longer a historical document.”

According to Bono, his father was “mind-blown by this.” I imagine that many readers may share the surprise at this rock star’s intimate faith.

SPIRITUAL PROVOCATEUR

For more than twenty-five years, Bono has been one of the most effective and enigmatic spiritual provocateurs. Who else talks to rock journalists about the theological superiority of grace over karma, writes the foreword to a specially-packaged book of Psalms, launched a conscience-raising line of clothing called Edun, and was seriously endorsed by the Los Angeles Times to head the World Bank? He makes pitches for the Bible (The Message) and has been nominated for two Nobel Peace Prizes.

Pope John Paul II wanted to wear his sunglasses when they met. Arch-conservative Senator Jesse Helms cried when he heard Bono describe the plight of hungry children in Africa. The U2 frontman single-handedly has done more to relieve third-world debt than all the Armani-clad finance ministers that could be packed into a United Nations conference room. He has a mysterious charisma, an unpretentious grace that affords him the allowance to be the only one wearing sunglasses indoors.

“When you’ve sold a lot of records, [laughs] it’s very easy to be megalomaniac enough to believe that you can change things. If you put your shoulder to the door, it might open. Especially if you’re representing a greater authority than yourself . . . ,” he confesses with confidence. “I promise, history will be hard on this moment. And whatever thoughts you have about God, who He is or if He exists, most will agree that if there is a God, God has a special place for the poor. The poor are where God lives. So these politicians should be nervous, not me.”

SHADE-WEARING FAITH

During his conversation with Assayas, Bono poetically stated: “Coolness might help in your negotiation with people through the world, maybe, but it is impossible to meet God with sunglasses on. It is impossible to meet God without abandon, without exposing yourself, being raw.”

His interlocutor responded: “What about your own sunglasses then? Do you wear them the same way a taxi driver would turn off his front light, so as to signal to God that this rock star is too full of himself and not for hire at the moment?”

Caught red-handed, Bono humbly responds, “You don’t know what’s going on behind those glasses, but God, I can assure you, does.”

Throughout his career, Bono has done his part to puncture the power of nihilism and hopelessness by pointing listeners to a transcendent reality of heaven, hell, angels, demons, deliverance, redemption, grace, and peace. U2’s lyrics unfold a world beyond the things that can be merely seen and rationally grasped.

Whether we want to or not, most of us create within our minds a picture and concept of God that fits neatly within a three-volume systematic theology text that we can proudly display on our bookshelves. Bono doesn’t buy that. He is a fan of the Psalms, Song of Solomon, Lamentations, and Job—books filled with anxiety, doubt, and loaded with questions. As he wrote in the foreword to the Psalms, “my religion could not be fiction, but it had to transcend facts. I could be mystical, but not mythical and definitely not ritual.”

During one conversation with Assayas about theology, Bono says, “It’s a mind-blowing concept that the God who created the Universe might be looking for company, a real relationship with people, but the thing that keeps me on my knees is the difference between Grace and Karma.

“You see, at the center of all religions is the idea of Karma. You know, what you put out comes back to you: an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, or in physics—in physical laws—every action is met by an equal or an opposite one. It’s clear to me that Karma is at the very heart of the Universe. I’m absolutely sure of it. And yet, along comes this idea called Grace to upend all that ‘As you reap, so will you sow’ stuff. Grace defies reason and logic. Love interrupts, if you like, the consequences of your actions, which in my case is very good news indeed, because I’ve done a lot of stupid stuff. . . . I’d be in big trouble if Karma was going to finally be my judge. It doesn’t excuse my mistakes, but I’m holding out for Grace. I’m holding out that Jesus took my sins onto the Cross, because I know who I am, and I hope I don’t have to depend on my own religiosity.”

DEALING WITH JESUS

The statement about Jesus on the cross sparks one of the most intimate and frank discussions in the entire book. “The son of God who takes away the sins of the world, I wish I could believe in that,” confesses Assayas.

“But I love the idea of the Sacrificial Lamb,” Bono replies. “I love the idea that God says: Look, you cretins, there are certain results to the way we are, to selfishness, and there’s mortality as part of your very sinful nature, and, let’s face it, you’re not living a very good life, are you? There are consequences to actions. The point of the death of Christ is that Christ took on the sins of the world, so that what we put out did not come back to us, and that our sinful nature does not reap the obvious death. That’s the point. It should keep us humbled. . . . It’s not our own good works that get us through the gates of Heaven.”

Still unconvinced, Assayas states frankly: “Such great hope is wonderful, even though it’s close to lunacy, in my view. Christ has his rank among the world’s great thinkers. But Son of God, isn’t that farfetched?”

“No, it’s not farfetched to me,” replies Bono. “Look, the secular response to the Christ story always goes like this: He was a great prophet, obviously a very interesting guy, had a lot to say along the lines of other great prophets, be they Elijah, Muhammad, Buddha, or Confucius. But actually Christ doesn’t allow you that. . . . He doesn’t let you off that hook. Christ says, No. I’m not saying I’m a teacher, don’t call me teacher. I’m not saying I’m a prophet. I’m saying: ‘I’m the Messiah.’ I’m saying: ‘I am God incarnate.’ And people say: No, no, please, just be a prophet. A prophet we can take. You’re a bit eccentric. We’ve had John the Baptist eating locusts and wild honey, we can handle that. But don’t mention the ‘M’ word! Because, you know, we’re gonna have to crucify you.”

Stepping into the argumentation of C. S. Lewis’s classic apologetics, Bono continues: “So what you’re left with is either Christ was who He said He was—the Messiah—or a complete nutcase. I mean, we’re talking nutcase on the level of Charles Manson . . . The idea that the entire course of civilization for over half of the globe could have its fate changed and turned upside-down by a nutcase, for me that’s farfetched.”

RELIGION IN ANSWERS

“How come you’re always quoting the Bible?” asks Assayas with a certain exasperation. “Was it because it was taught at school? Or because your father or mother wanted you to read it?” In response, Bono tells the story of attending a Christmas Eve service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin and describes the moment when the incarnation really made sense to him.

“The idea that God, if there is a force of Love and Logic in the universe, that it would seek to explain itself is amazing enough,” he said. “That it would seek to explain itself and describe itself by becoming a child born in straw poverty, in [excrement] and straw . . . a child . . . I just thought: ‘Wow!’ Just the poetry . . . Unknowable love, unknowable power, describes itself as the most vulnerable.”

Behind a huge pillar, during the singing is when the epiphany occurred. “I was sitting there, and it’s not that it hadn’t struck me before, but tears came down my face, and I saw the genius of this, utter genius of picking a particular point in time and deciding to turn on this,” he said of the birth of Christ. “Love needs to find form, intimacy needs to be whispered. To me, it makes sense. It’s actually logical. It’s pure logic. Essence has to manifest itself. It’s inevitable. Love has to become an action or something concrete. It would have to happen. There must be an incarnation. Love must be made flesh.”

I am fairly confident that much of this conversation is jaw-dropping to many U2 fans around the world—as well as to some Christian critics of Bono and the band. After all, these are not the kinds of public conversations a reader expects to hear from a jet-setting rock star.

One of the chapters is titled “Add Eternity to That,” and it is a log of their conversation that took place one week after the Madrid train bombings on March 11, 2004. The terrorist attack left 191 dead and more than 1,800 injured. During this interview, Bono attempts to clarify between faith in Christ and the fanaticism of terrorism.

“My understanding of the Scriptures has been made simple by the person of Christ. Christ teaches that God is love. What does that mean? What it means for me: a study of the life of Christ,” Bono says. “Love here describes itself as a child born in straw poverty, the most vulnerable situation of all, without honor. . . . God is love, and as much as I respond [sighs] in allowing myself to be transformed by that love and acting in that love, that’s my religion. Where things get complicated for me, is when I try to live this love. Now, that’s not so easy.”

Perhaps these conversations with a French journalist help explain the beauty, relevance, and longevity of Bono’s career. He is brutally honest about his shortcomings, as well as his hope for redemption. “But with Christ,” he testifies, “we have access in a one-to-one relationship, for, as in the Old Testament, it was more one of worship and awe, a vertical relationship. The New Testament, on the other hand, we look across at a Jesus who looks familiar, horizontal. The combination is what makes the Cross.”

Steve Beard is the creator of Thunderstruck.org. This article first appeared in the December 2005 issue of BreakPoint WorldView magazine.